Capturing and storing value from CCS [NGW Magazine]

The UK has had a few false starts with carbon capture and storage projects using third-party, industrial emissions, but now a project is closer to completion than any of its predecessors. Missing is the crucial support mechanism, which also proved a fatal problem for past schemes. The UK government’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (Beis) expects to have a plan for that this year, though.

UK privately-owned Pale Blue Dot is now finishing the groundwork of its Acorn offshore carbon capture and storage project, believing it has good answers to the technical questions that have arisen. It just needs investors.

As part of its funding requirement it hosted a knowledge-sharing seminar in London January 23, where geologists, environmental consultants and PBD itself were among those who presented their findings.

PBD has got where it is quickly with the help of funding from Accelerating Carbon Capture, Use and Storage Technologies (ACT), now an international group, of which the UK was one of the nine founding European – but not all European Union -- countries, and part-funded by the European Commission. Norway is also a member.

Beis spokesman Brian Allison told the event that PBD’s CCS Acorn project is a great project. Funding comes to an end February 29, 18 months from funding began, by which time it will have met all the requirements in terms of sharing knowledge.

PBD CEO Alan James said ACT had moved Acorn to the point where it can be piece of “real infrastructure, and that Beis had enabled it to reach positive outcomes at an early stage.”

But the question now is, what more can government or industry do, since without some form of intervention CCS in the UK will not succeed. The carbon price would need to be a lot higher than it is, or demand for hydrogen needs to grow very fast, for example.

And time is of the essence. Keeping an offshore pipeline ready for re-use is expensive but once it has been decommissioned, the opportunity has gone. Replacing it with a new pipeline later will not only cost a lot more but generate even more emissions in the manufacturing and installation processes. As rigs and wells are all different in their engineering, the focus of the project has been on re-using just the pipelines.

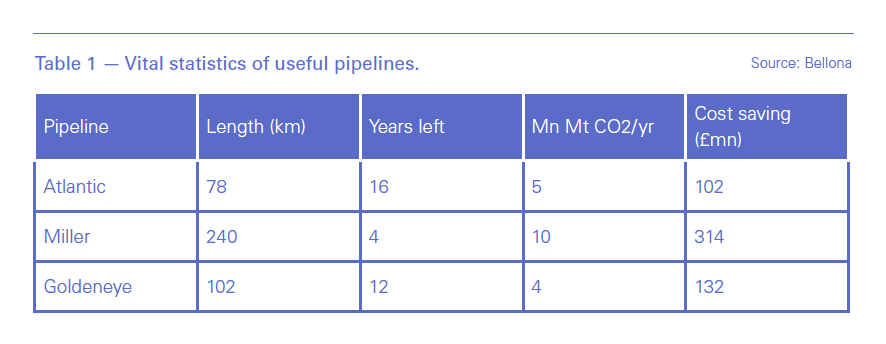

According to ACT-funded research by Bellona Foundation, there are 580 pipelines in the North Sea due to be decommissioned between now and 2025, but there is no business case yet for CCS use, meaning the window of opportunity for re-use is closing.

The most suitable for St Fergus are the Atlantic, the Goldeneye and the Miller gas system pipelines, said Bellona’s Keith Whiriskey. The transfer of liabilities and compensation for preservation are important considerations for the operators. “They need a rationale to save the pipelines: the government needs to remove the fog over CCS and say the lines will be needed at some future date,” said Whiriskey, who also suggested that a central, competent body for CCS might be needed to take over the lines.

One such pipeline, running from the Shell-operated Goldeneye field, has been filled with fluid while its fate is decided. It can theoretically carry up to 17mn mt/yr, one of the delegates told NGW, if compression is added, although the nominal volume is a quarter of that, and the operators need to be more transparent about the actual capacity.

The onshore high-pressure pipeline, now operated by National Grid, could be deregulated, outside the usual price control process; or it could be sold off, depending on how talks go. Studies done in the past for other CCS projects have already proved that the Feeder 10 pipeline could be reversed to take CO2 back to St Fergus. St Fergus could also house a steam methane reformation plant to remove the CO2 which would then go straight back offshore.

But Feeder 10 is only one possible route: the CO2 could also be shipped to St Fergus from continental Europe or from elsewhere in the UK.

The geology of two offshore storage sites, Acorn and East Mey, has been tested to destruction so that the operators know how much pressure the rocks can take, how fast the gas can move through them and hence the safe injection rates. “You generally need to have two plans,” James told the conference. “One is a fall-back plan and the other is a build-out.”

Producers such as Repsol and Nexen have helpfully provided core samples of both the sandstone and the capstone to test for retention and for impermeability and the research laboratories found them ideal. “We don’t want the wells to fail at high-pressure injection,” geologist Richard Worden, a professor at Liverpool University, told the seminar.

Both storage sites are highly suitable for the injection and long-term storage of CO2. Both the Captain and Mey Sandstones are highly porous and permeable, with rock chemistry that is stable in CO2-rich conditions. The Mey Sandstone has a greater rock strength than the Captain Sandstone owing to its lower overall porosity. All the samples tested were strong enough to withstand expected pressures/stresses during CO2 injection operations and long-term storage, PBD says.

Acorn could hold 152mn mt injecting at 5mn mt/yr, at an offshore cost of £172mn; East Mey could hold 500mn mt CO2 injecting at 5mn mt/yr and cost £372mn.

All going well, the operator will take final investment decision by the end of 2020; the first injection well will be drilled in 2022; and the process will be underway by 2023. That first well will be able to handle 2mn mt/yr, of which maybe 500,000 mt/yr will come from stripping out the carbon at St Fergus. By the end of the 2020s, the storage plant’s capacity could be fully sold out, but work will have begun on a second plant.

Phase 1 is costed at £276mn ($360mn) all in, for 200,000 metric tons/yr but it would have enough capacity to inject 2mn mt/yr if that was the next step. That excludes the cost of steam reformation but includes the monitoring of leaks, which will be essential to satisfy the regulators.

Whatever the technology used to remove the hydrogen, and steam reformation might be superseded, there is little doubt that hydrogen will play a vital part in the future energy mix as it can displace two thirds or three quarters of the emissions from the heat and transport sector. As Bellona said, it is very difficult to decarbonise without CCS.

So the focus now is shifting from the science to the economics. Industry needs a reason to invest in it, as the costs of carbon capture and storage at a site level before injection into the offtake point are very high, let alone the high-pressure part of the operation.

A lot of heat is needed to run the chemical process of carbon capture using amine technology, for example. “We are happy with the story,” one major emitter told NGW, “but the question is how much is society is prepared to pay for it.” Some sites could have to spend upwards of £80/metric ton on collecting the flue gas into one place so that the CO2 may be extracted and exported from the site, he said. At the moment, the EU carbon price is in the mid-€20s/mt.

Investors have been talking to PBD about it, but what carbon price would be needed to support it, or how much public funding might be available, are difficult questions for PBD to answer publicly. James told NGW that a mix of public and private capital might be needed; perhaps a significant public investment would trigger the confidence of the private sector, allowing the state to retreat later.

Beis told NGW January 30 that the government’s ambition is that the UK should have the option to deploy CCUS at scale during the 2030s, subject to costs coming down sufficiently.

It said it would start detailed engagement with industry on the critical challenges to delivering CCUS in the UK this year, and key elements of those talks will be the cost structures, risk sharing arrangements and the necessary market-based frameworks.

In parallel to funding individual projects it said it was investing in cost reduction and technological development by putting £45mn into CCUS innovation programmes between 2017 and 2021. The government has also announced it will complete its Review of the Investment and Delivery Frameworks for CCUS in 2019.

Some private capital might come from the Oil & Gas Climate Initiative: if the majors who set it up want gas to have a long-term future, they might have no choice but to plough some of their profits into schemes that enable decarbonisation. They are already engaged on a scheme based at Teesside, from where the CO2 might be shipped north or disposed of nearer home. Total has also contributed funding to Acorn, and is involved in Equinor’s Northern Lights project (see box).

Norway might get there first

State-owned Equinor and its partners French Total and Anglo-Dutch Shell are carrying out a feasibility study on behalf of the Norwegian government into CO2 storage on the continental shelf, not far from the giant Troll oil and gas field. The energy ministry will take a final investment decision in 2020 or 2021.

The full scale CCS-project could become the first carbon storage project in the world to receive CO2 from industrial sources in several countries, Equinor told NGW by email.

The CO2 will be captured from onshore industrial plants in eastern Norway and transported by ship from the capture area to the onshore reception plant. At this plant, the CO2 will be pumped from the ship to onshore tanks before it is sent in a pipeline and injected for permanent storage 1,000-2,000 metres below the seabed.

The project will be prepared for further expansion of capacity to receive additional CO2 volumes, with the aim of stimulating new commercial carbon capture projects in Norway, Europe and other countries around the world. And if the Norwegian CCS demonstration project is realised with a large storage hub on the NCS, this may open up for future CO2 storage from other projects, including hydrogen production, Equinor said.

The purpose of the project is to prove that the CCS technology can be supplied to a future market. It will focus on proving technical, operational, regulatory and commercial set-up of the CCS value chains aiming to stimulate new CCS projects and enable further expansion phases of the Norwegian project.

Equinor has more than 20 years' experience of CO2 storage from Sleipner and Hammerfest LNG. Through its operational experience, it says it has a better understanding of how the reservoir is affected by CO2 injection and how it efficiently can monitor the CO2 location in the reservoir.

Equinor sees CCS as a leading technology for decarbonising fossil fuels and an important long-term measure for reducing CO2 emissions globally. Equinor believes a cost for carbon is vital in order to make this commercially viable.

It said: “We support a cost for carbon and believe this would incentivize the supply and use of lower carbon options, enabling the world to move faster to sustainable energy while meeting growing demand along the way. We work with governments, businesses and organisations to set an effective price for carbon around the world. In Norway, Equinor already operates successfully with the highest carbon tax in the world.”

Industry must do the heavy carbon lifting: survey

According to DNV GL’s annual survey of the industry, the vast majority (78%) of senior oil and gas professionals believe that their industry will only decarbonise if it makes financial sense for them to do so. And most (56%) believe that the industry, rather than governments, should take responsibility for the uptake of carbon capture and storage (CCS).

This is the main reason why CCS has seen limited uptake in the oil and gas industry since its inception in the 1970s.

DNV GL’s 2018 Energy Transition Outlook says 22 CCS facilities are in operation, of which 12 are in North America and have viable business cases because they use the CO2 for enhanced oil recovery. US initiatives also benefit from tax credits, with no cap on how much can be injected underground.

Government interventions, either through capital funding or regulatory incentives, are still necessary to make most CCS initiatives viable.

The Gorgon project in Australia, for example, has committed to storing the carbon it produces, as part of its licence to operate an LNG facility on Barrow Island. Elsewhere, the Sleipner and Snohvit storage projects offshore Norway benefit from a Norwegian carbon tax.

Only a few (13%) of its survey respondents believe that a carbon-pricing model will be implemented in 2019, and 41% believe there will never be a globally effective carbon price.