Canada dry back on tap? [NGW Magazine]

Crude oil demand is in for a steep fall in the coming months as travel for work and pleasure shrinks and industrial demand falls. The International Energy Agency earlier forecast a 20mn barrels/day drop, while the chief economist for global commodities trader Trafigura has been even more bearish, suggesting in late March that global crude demand could fall by 30mn b/d in April.

But the crude market collapse could actually provide something of a bright light for Canada’s beleaguered gas producers. Drillers in the US basins such as the Permian and Eagle Ford cut spending. Reduced shale oil production means reduced associated gas production from those wells, putting upward pressure on natural gas prices – which have floundered in recent years – in both Canada and the US. Some estimates have put the impact on US gas production as high as 14bn ft³/day, or about 145bn m³/yr.

Benchmarks hit hard

The international Brent crude marker, which opened the year around $70/b, has since dropped to as low as $25/b, while the North American benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) has plunged to the low teens from more than $60/b in early January. As March drew to a close, Permian crude fell to $13/b, its lowest since 1999, and on March 30, WTI dipped briefly below $20.

Although Saudi Arabia, Russia and other producers – working as a new Opec++ group – managed to reach agreement in April to reduce production by nearly 10mn b/d over the next few months, the cuts aren’t nearly enough to cover initial projections of a 20mn b/d drop in demand, much less emerging consensus that the demand destruction could reach as high as 30mn b/d.

The modest reductions served to stabilise benchmark crude prices, to some extent, with Brent settling in around $30/b by mid-April and WTI hovering around $20/b, but with some upside evident in forward contracts: June was at $27/b, July at around $32/b and August at about $33/b.

But as May contracts for WTI on the Nymex futures exchange – a proxy for spot physical prices – approached expiry on April 21, any imagined stability resulting from the Opec++ accord had disappeared. On April 20, for the first time ever, a front-month crude contract ended trading in negative territory: May WTI closed the day at -$37/b as traders unloaded their paper barrels before facing the prospect of taking delivery of physical barrels in a market virtually drowning in surplus crude.

Most estimates suggest that break-even prices for shale oil in the Permian range from about $25/b to nearly $40/b, while Goldman Sachs, in a pre-crash report, said Chevron – which in mid-March slashed its capital expenditure plans for 2020 by 20%, or about $4bn – needs $50/b oil to finance its operations and cover its dividend. ExxonMobil, the world’s biggest public oil and gas company, needs oil above $70/b to finance its operations and pay shareholders their dividends, according to some analysts.

Permian cuts will lead

Crude oil from the Permian basin in Texas, as well as from other shale oil basins like the Eagle Ford and the Bakken, in North Dakota, is among the highest-cost on the planet – and the obvious target of the Russians when they pulled out of the Opec+ cohort. But natural gas produced along with the shale oil is a significant source of US gas production, and any cuts in crude production will lead, inevitably, to lower gas production.

The question, then, isn’t if US shale production will decline; it’s more a matter of when, and by how much, and signs are already emerging that reduced production is imminent.

Field activity statistics are normally the first sign that production will decline, and already, drilling is starting to slow: in March alone, according to service provider Baker Hughes, the active rig count in the Permian basin fell by nearly 10%, to 382 active rigs in the week ended March 27 from 415 in the week ended March 6. In Canada, the count was nearly halved in just one week, to 54 in the week ended March 27 from 98 the prior week, while across North America, 88 rotary rigs were idled between March 20 and March 27, dropping the count to 782 from 870. A year ago, according to Baker Hughes data, 1,094 rotary rigs were at work in North America.

By the middle of April, the rig count in the Permian had fallen to 283 rigs, the lowest since February 2017. The gas rig count, meanwhile, fell another seven – three each in the Marcellus and Haynesville plays and one in the “Other” category.

Rig activity in free-fall

In April, consultancy Rystad Energy suggested oil-focused horizontal drilling in the US could ultimately fall by as much as 65% from mid-March levels.

From a peak this year of about 620 rigs in mid-March, the oil rig count is forecast to free-fall to a potential bottom of around 200, Rystad estimated, basing its forecast on updated guidance from exploration and production companies. Most of the anticipated decline will come by the end of April – the horizontal rig count has so far dropped to roughly 500 Rystad said in its April 7 report, falling by 19% from the recent peak just three weeks ago.

“The speed of this decline exceeds the initial post-oil-price-crash expectations,” Artem Abramov, Rystad’s head of shale research, said. “This is for sure a much faster industry reaction than during the previous US land rig down cycles, and we will likely see continuous downward adjustments of similar magnitude throughout the next couple of months.”

With drilling activity falling, the next activity decline will be seen by the service providers – those companies that complete, frac and maintain the shale wells.

Two of the world’s biggest oilfield service companies – Schlumberger and Halliburton – have announced significant spending cuts: Schlumberger will cut 2020 spending by 30% from 2019 levels and laid off 1,500 workers in the first quarter; Halliburton has furloughed 3,500 workers for two months, and is reportedly considering capital expenditure reductions of up to 65% for this year.

On April 17, Schlumberger reported a pre-tax loss of $8.09bn, almost all of which reflected a largely non-cash pre-tax charge of $8.5bn, relating to the impairment of goodwill, intangible assets and other long-lived assets as a result of the “significant decline in market valuations during March 2020.”

And more is set to hit the company in Q2 2020, CEO Olivier Le Peuch told Schlumberger’s Q1 conference call.

“We anticipate both rig activity and frac completion activity to continue to decline sharply during the second quarter to reach a sequential decline of 40% to 60%, which matches the full-year budget adjustment guidance shared by most operators in North America land,” he said. “This would represent the most severe decline in drilling and completion activity in a single quarter in several decades.”

Three days later, Halliburton posted a $1.02bn Q1 2020 loss, mostly related to a $1.1bn impairment charge taken to reflect new cost structures in the current market. Capital expenditures, it said, would be cut by 50% this year, to about $800mn, while overhead and other cost reductions totalling about $1bn have been targeted.

Combined impacts of the Covid-19 containment measures and the global crude oversupply, CEO Jeff Miller said, will be most sharply felt in Halliburton’s North American operations.

“Our industry is facing the dual shock of a massive drop in global oil demand coupled with a resulting oversupply,” he said. “Consequently, we expect activity in North America land to sharply decline during the second quarter and remain depressed through year-end, impacting all basins.”

As drilling and completion activity withers away, how quickly activity slows in high-cost, short-cycle basins like the Permian could be critical for Canadian natural gas producers, especially dry gas producers whose output – unlike the cheap natural gas associated with Permian oil production – isn’t so tightly tied to world or North American oil prices.

By mid-April, the Permian decline was evident: on April 13, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), in its monthly drilling productivity report, projected Permian crude oil production would average 4.6mn b/d in April and 4.5mn b/d in May. March production averaged 4.7mn b/d; February was at 4.8mn b/d.

And shale gas production was also starting to slide, the EIA said. Projected production in April was about 84.03bn ft3/day, down from the EIA March forecast for April at just under 85bn ft3/day, while May production was seen at less than 83.2bn ft3/day.

The North American gas market is now in the weak demand shoulder months of April and May – winter heating demand is in the rear view mirror and summer cooling demand has yet to ramp up – so Canadian dry gas producers will see little in the way of price movement in the near-term, Bill Gwozd, a Calgary gas industry consultant with Argo Consulting told NGW. But neither are big declines expected.

“Due to the timing of warmer weather coming up in April through September, gas demand tilts down a fair bit, so even if oil producers in the Permian basin gear down oil production (and associated natural gas production), gas demand will already be sliding downwards due to the warmer summer weather,” Gwozd said. “However, if the low oil prices persist into the winter months, then dry gas producers would be needed to make up the shortfall.”

Gas prominent again

Darren Gee, CEO of Peyto Exploration & Development, which is mainly active in the drier Deep Basin of west central Alberta, said he’s already seeing encouraging movement in the Aeco spot price, the Canadian equivalent of the US Henry Hub.

“Gas does appear to be the bright light today, especially Aeco gas prices,” he told NGW. “The forward curve has held up surprisingly well, especially for the low-cost guys – the key will be keeping the gas flowing if the liquids have nowhere to go.”

Data from Gas Alberta shows the Aeco C futures price trending steadily higher through February 2021, when it reaches C$2.71/GJ. On April 21, the Aeco C spot price stood at C$2/GJ.

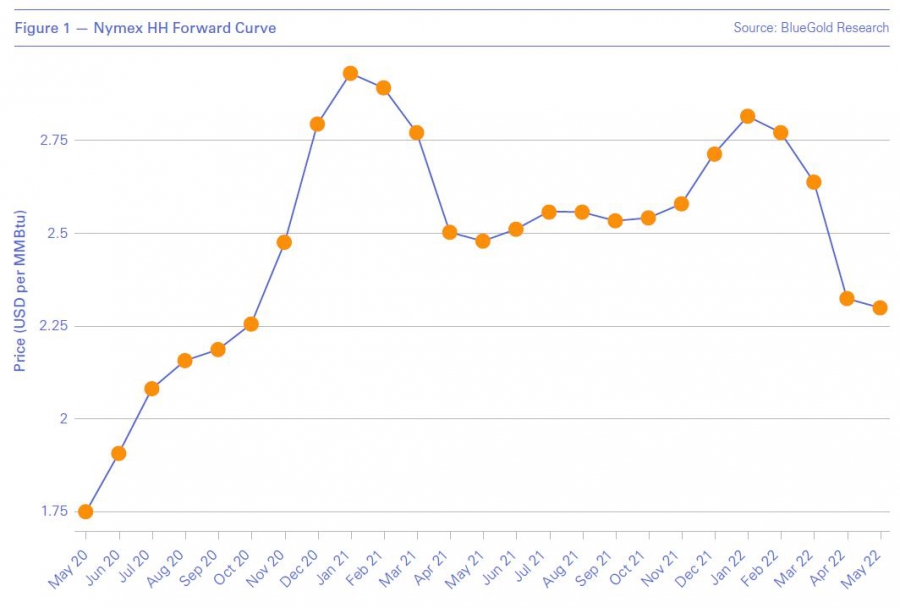

The Henry Hub forward curve is showing similar strength, according to data from BlueGold Research: from a May 2020 price of US$1.75/mn Btu it rises steadily through the rest of this year, reaching nearly US$2.90/mn Btu for January 2021 contracts.

There is little capacity to store condensate, the most valuable liquid component of natural gas and used primarily as a diluent for produced bitumen from the oil sands. Without significant storage capabilities and bitumen production expected to decline, Gee said, producers will have to shut in their liquids-rich gas or bypass systems that extract the liquids by cooling the gas stream.

“At Peyto, we’re shutting off our deep cut plant and warming up all our refrig[eration] processes to reject as much liquids as we can and leave it in the gas, where we get paid for the higher heat content,” he said. “The result is lower total production on a barrel of oil equivalent basis, but more revenue (from a higher realised price for the rich gas). That matters, and today, cash is king.”

Demand for natural gas, Gwozd said, is also expected to hold up through the Covid-19 pandemic, as about 85% of the gas consumed in Canada is used for utility purposes: to heat homes and provide fuel for cooking and power generation – essential services during the current lockdowns that span the globe.

That stands in stark contrast to the liquid fuels market where demand for crude oil and refined products has fallen off the table since the pandemic was declared: in the US alone, road traffic is down by 50% and air travel is off by 90% from pre-pandemic levels.

“Utility gas demand should be fairly constant in a virus world since homes and lights are still used,” Gwozd said. “Manufacturing (plastic water bottles, shirts, and fertilisers for example) may have minor deferments, though on an annualised basis, demand will still be fairly flat.”

Any blips in gas demand resulting from Covid-19 and measures taken to respond to the pandemic, he said, would likely be masked by weather-related changes – an observation shared by the lobby group representing most of Canada’s biggest oil and gas producers.

Mark Pinney, manager, markets and transportation for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), told NGW there could be minor upsets in domestic gas demand in Canada, with varying degrees of impact in different sectors of the economy.

“In the longer term, however, there remains an opportunity for growth in Canada’s natural gas sector as the international community will still be faced with the need to control global greenhouse gas emissions,” he said in an email.

In the residential and commercial sectors, which account for about a third of Canadian gas demand, consumption through the pandemic will likely still be influenced by weather, Pinney said, while most of the remaining demand is for process heat and feedstock requirements in the industrial sector and for power generation.

“There is also a relatively minor component of natural gas demand related to transportation,” he added. “Demand in these sectors is likely to be more directly impacted in the short term as economic activity is affected by Covid-19.”

Canadian producers sitting prettier

Even with sectoral movements in gas demand – some related to Covid-19, some to weather – the overall demand for natural gas in North America is not going to disappear, pandemic or not, the head of Canada’s main gas transportation provider said in early April. And Canadian producers are well positioned to meet that demand.

“The demand for gas isn’t going away - the question is where will that gas come from,” TC Energy CEO Russ Girling told the Scotiabank CAPP Investment Symposium, held online April 7-8. “Right now we continue to believe that the low-cost basins – western Canada, the Appalachian region – will be where that gas comes from.”

The WCSB remains one of the lowest-cost basins in North America, he said, and demand for gas will continue to grow, led by power generation, as generators in Alberta and Saskatchewan switch from coal to gas, and LNG projects in BC and Nova Scotia.

“Even as we speak, a large part of the demand for gas is space heating, petrochemicals, power generation – all of those things continue, even through this crisis, which is why we’ve got our people working so hard to ensure there is no disruption in supply,” Girling said.