Brave New World: Emerging Trends in Vietnam’s LNG-to-power sector

Vietnam’s energy transition has been closely watched in recent years. The highly anticipated Power Development Master Plan 8 (“PDP8”), which will outline Vietnam’s plans for securing its anticipated electricity needs from 2021 to 2030, is expected, when it is finalised[1], to mark a significant shift away from coal towards cleaner forms of energy. This policy trend was evidenced by Prime Minister (“PM”) Pham Minh Chinh's announcement targeting net-zero emissions by 2050 at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (“COP26”).

LNG-to-power remains a significant component of Vietnam’s energy transition story and investors – both domestic and global – continue to show immense interest in the sector, as tendering and awarding of projects by the Vietnam government continues notwithstanding the continued challenges of COVID-19. Despite these promising tailwinds, no international developer-led project has commenced construction or achieved commercial operations to date and the market is very much still finding its footing in this new terrain. Drawing from our experience advising on early-stage LNG-to-power projects both in Vietnam and internationally, this article includes some of our main observations, key challenges for investors, as well as potential strategies for addressing these issues.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

Adopting the right model

Finding the right legal regime

In the past, major power projects in Vietnam typically have been developed under Vietnam’s public-private partnership (“PPP”) investment regime,[2] given the various incentives and government support afforded to investors under this route (including government guarantees and a highly-developed power purchase agreement that was generally regarded as bankable by international financiers). Initially many in the market had anticipated that the currently-proposed wave of LNG-to-power projects in Vietnam similarly would be developed as PPP projects. However, perception of the attractiveness of the PPP route is changing, especially in light of the introduction of the latest Law on Public-Private Partnership in January 2021 (“New PPP Law”). As has been widely commented on in the market, the New PPP Law appears to signal an evolution in the Vietnamese government’s approach to foreign investment, marking a significant reduction in the scope of investor protections and support on offer compared to what had been provided under the previous regime. Moreover, since it came into effect the Vietnam government has demonstrated an apparent reluctance to actually approve major PPP projects under the New PPP Law.

In this context, despite original expectations, a number of international investors in fact are increasingly gravitating towards developing their Vietnam LNG-to-power projects under Vietnam’s general laws on investment and enterprises (often referred to in Vietnam as the “IPP” model), given among other reasons its potentially shorter timeframe for implementation, and are seeking to negotiate their additional investor and bankability requirements with the PM, the Ministry of Industry and Trade (“MOIT”), Vietnam Electricity (“EVN") and other relevant stakeholders in hopes of achieving a favourable outcome, although early indications from pathfinder projects and some of the government's initial project tender processes suggest that, as might be expected, such negotiations in themselves are likely to be lengthy and complex affairs (for some of the reasons set out below).

Figure 1: PPP projects vs IPP projects

|

|

PPP Projects (prior to PPP Law) |

PPP Projects (following PPP Law) |

IPP Projects |

|

|

Form of PPA |

Market-tested bankable contracts. |

PPP Law introduces requirement for standard-form contracts to be used, but these contracts have not emerged. |

Standard-form PPA attached to Circular No. 57. Form of PPA generally regarded as more suited for local financing, and does not cover many key bankability issues required by international lenders. Additional investment protections and inclusion of bankability requirements will be subject to approval from the Electricity Regulatory Authority of Vietnam. |

|

|

Take or Pay (“TOP”) |

Generally available. |

To be determined when standard-form contract emerges. |

No TOP, deemed commissioning or deemed dispatch provisions in standard-form PPA. |

|

|

Government guarantees |

Performance obligations |

Government guarantee covering the performance or payment obligations of state counterparties contained in Decree 63/2018/ND-CP dated 4 May 2018 (“Decree 63”). |

Government guarantee in Decree 63 no longer reflected in PPP Law.

|

No specified basis for government to guarantee obligations of state counterparties. |

|

Foreign currency |

Government guarantee and undertaking that USD will be available. |

30% guarantee of availability of foreign currency. |

No specified basis for guarantee of currency availability and convertibility. |

|

|

Termination payments |

Generally available. |

Termination payments are payable only if the concession agreement is terminated due to national interest or national defence, or a MOIT event of default. No termination payments available for prolonged force majeure. |

Not specifically available. |

|

|

Governing law |

Typically English law. |

Vietnamese law |

Vietnamese law |

|

Selecting the right corporate structure

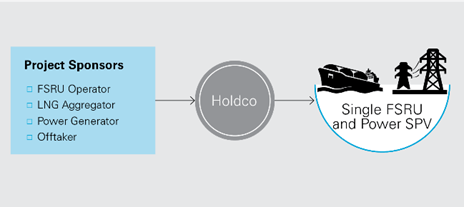

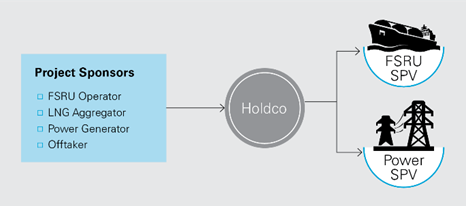

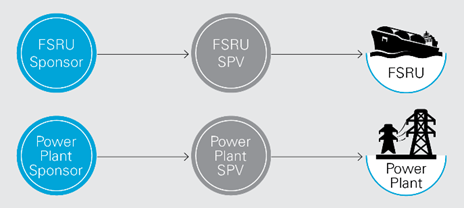

Given that a LNG-to-power project comprises of multiple components (including the LNG terminal and the power plant), in Vietnam, as with in other jurisdictions, investors continue to look at various integrated and non-integrated corporate models to structure the ownership of these components. In determining which corporate structure is most appropriate for their project, no “one-size-fits-all approach” is emerging in Vietnam and investors are needing to evaluate Vietnam government and regulatory requirements, tax considerations, financing/bankability considerations, sources of and markets for LNG/gas alongside their own specific commercial and other requirements and those of the project. Figure 2 below sets out some ownership models that we are seeing being considered by investors for their Vietnam LNG-to-power projects, along with advantages and disadvantages that these investors are identifying with each structure in the Vietnam context.

Figure 2: Corporate structures (assuming a floating regasification unit (“FSRU”) LNG facility)

|

Model |

Structure Diagram |

Comments |

|

Separate Ownership Model

|

|

|

|

Hybrid-Ownership Model |

|

|

|

Consolidated Model |

|

|

Persisting regulatory challenges

The regulatory environment (or lack thereof) in Vietnam continues to present a challenge to LNG-to-power developers, especially for international investors new to the market. The regulatory approval process for LNG-to-power projects in Vietnam remains lengthy, complex and highly dependent on the discretion of granting authorities and this is further complicated by the involvement of numerous granting authorities/government agencies. Moreover, Vietnam is making slow progress in developing its legal framework for LNG-related businesses, with little sign of things dramatically improving in the near future. For example, as the LNG market in Vietnam is in early stages of development, limited legislation (namely decree 87/2018/ND-CP) has been enacted to specifically govern the import, transport and trading of LNG, with no detailed regulations to provide guidance on practical implementation (and in particular existing regulations are silent on the use of floating storage / regasification).

Land issues in particular remain a key investor concern for a number of reasons, including the challenges arising due to the prohibition on. private ownership of land and the lengthy land allocation process, as well as the complexity and uncertainty around granting land-related security to financiers (including, in light of recent developments to the PPP and IPP regime, how well-established issues such as restrictions against land use rights being mortgaged to foreign lenders will be addressed, as well as more novel questions arising in the context of LNG-to-power projects specifically such as how security over sea use rights can be granted).

Conclusion

As a number of the LNG-to-power prospects in Vietnam start moving from blueprint phase into early stage implementation it perhaps comes as no surprise to market observers that developers are finding themselves faced with major question marks as to the optimal path forward, even as they prepare to pay their not-insignificant tender or investment deposits[3]. Despite this, momentum remains palpable as investors vying to be at the forefront of this game-changing sector, supported by on-the-ground teams or local partners, forge ahead with developing the right investment models for their projects navigating regulatory intricacies and engaging governmental and other stakeholders on the bankability landscape ahead of them. The race is on and, with the variety of players and approaches being adopted in the market, it will be a thrilling dash to the finish line.

[1] Latest reports indicate that current revisions being made to the draft PDP8 by Ministry of Energy and Ministry of Industry & Trade are expected to be completed by early 2022.

[2] ACSV, LNG-to-Power Projects in Vietnam and Key Legal Issues, para 2.2.

[3] Between 1 and 3 per. cent of project value.

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.

.png)