BP Predicts Faster Decline In Gas Demand [Gas In Transition]

According to BP’s Global Energy Outlook 2022, published in March, peak oil and gas demand will not happen until 2030 and 2040-2050 respectively. Without major change, this could be the likely outcome.

The new outlook uses three scenarios to explore the range of possible pathways for the global energy system to 2050:

· The New Momentum scenario “captures the broad trajectory along which the global energy system is currently progressing.” It places weight both on the marked increase in global ambition for decarbonisation seen in recent years and the likelihood that those aims and ambitions will be achieved, and on the manner and speed of progress seen over the recent past.

· The Accelerated scenario explores how different elements of the energy system might change in order to achieve a substantial reduction in carbon emissions. It assumes that there is a significant tightening of climate policies leading to a pronounced and sustained fall in CO2.

· The Net-zero scenario goes further than the Accelerated scenario, also assuming a shift in societal behaviour and preferences which further supports gains in energy efficiency and the adoption of low-carbon energy sources.

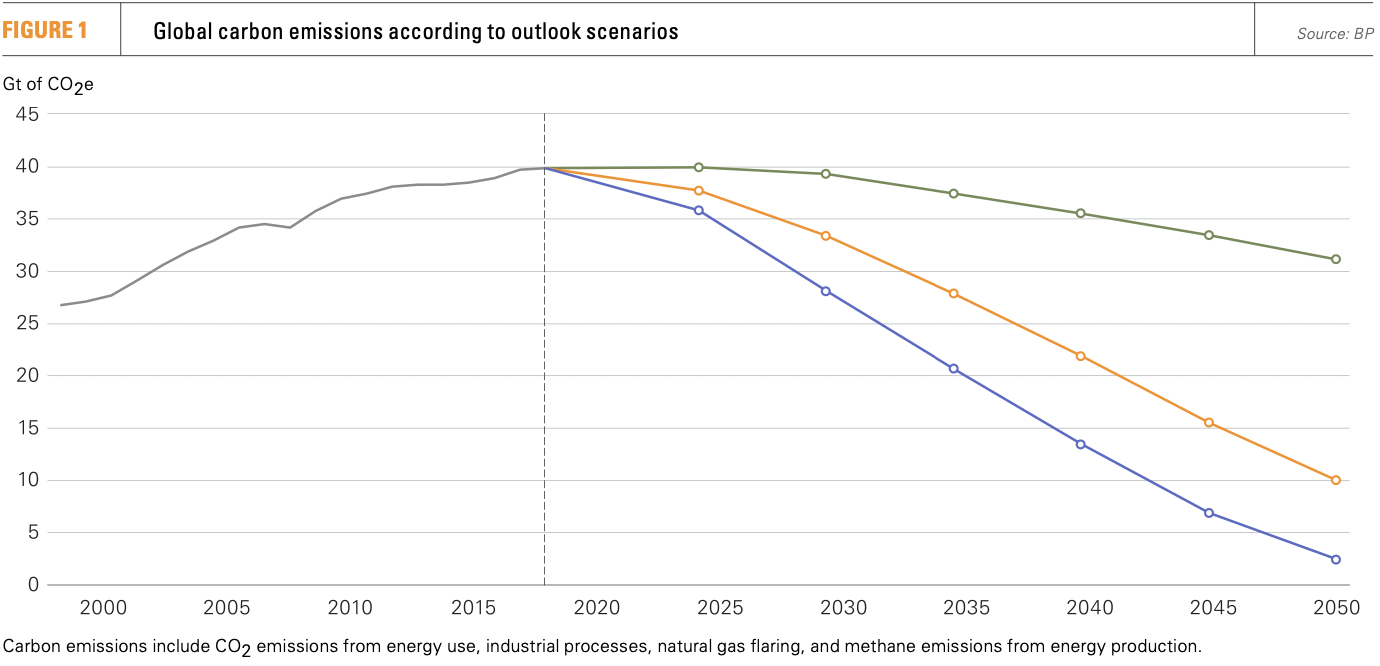

In other words, the Accelerated and Net-zero scenarios assume a significant shift in measures to reduce carbon emissions over and above the trajectory the world is following now (figure 1).

These scenarios were largely prepared before the outbreak of war in Ukraine and do not include any analysis of its possible implications for economic growth and global energy markets. As Spencer Dale, BP chief economist, points out in the introduction to the outlook, “those implications could have lasting impacts on global economic and energy systems and the energy transition.” The longer the war takes the more likely this becomes.

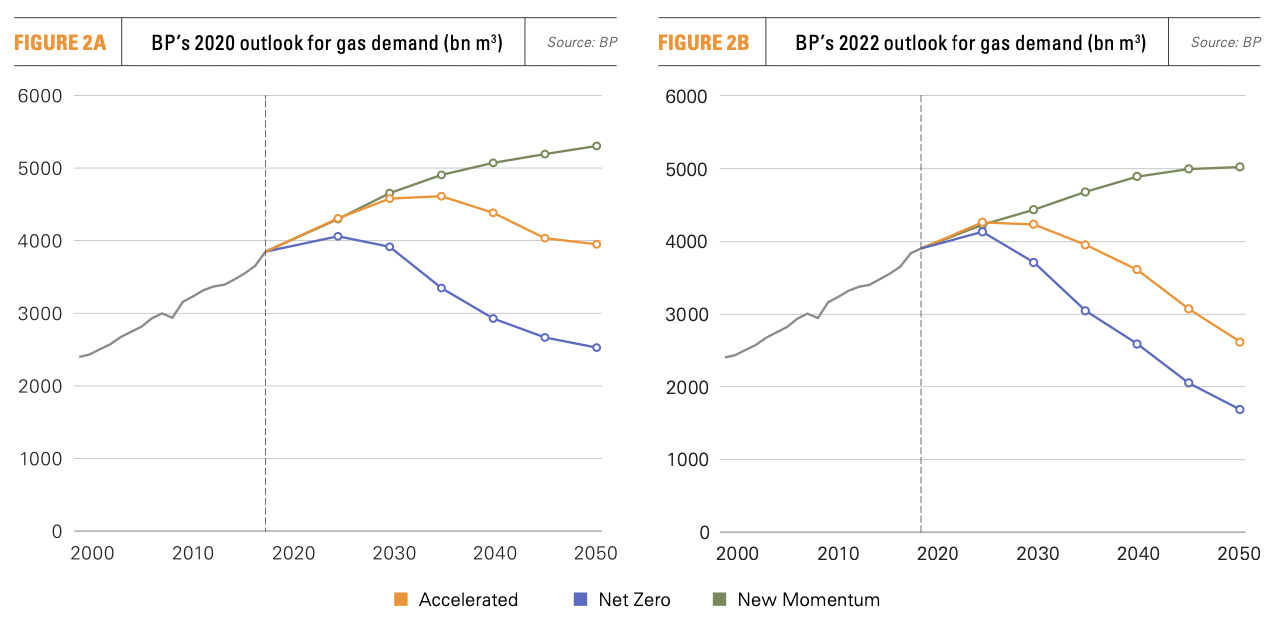

The Accelerated and Net-zero scenarios are broadly in line with the Paris Agreement. In order to realise these, the 2022 outlook expects natural gas demand to peak early, by 2025, declining by 35% and 60% by 2050 respectively (figure 2b). In the previous 2020 outlook, peak demand under the Rapid scenario does not happen until 2035, with only a modest 15% decline by 2050 – the previous Net-zero scenario peak occurs in 2025, but with the decline a lot slower, at 35% by 2050 (figure 2a). This reflects a falling use of gas in industry and buildings, due to a faster switch to low-carbon energy sources in the 2022 outlook.

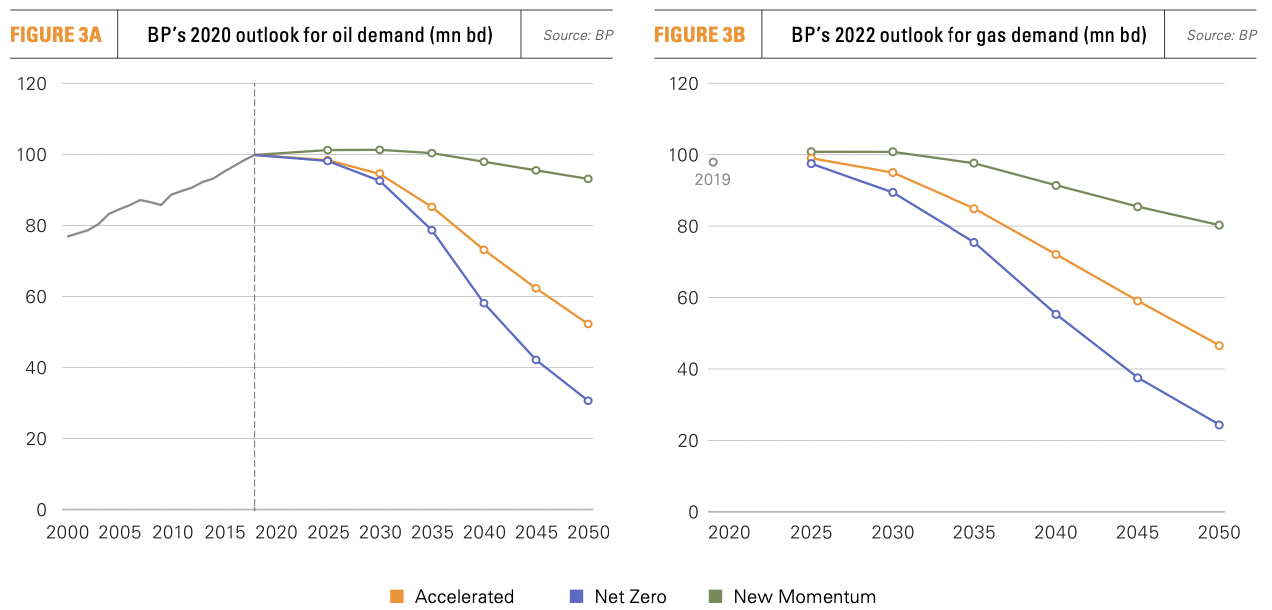

Contrary to the 2020 edition of the outlook, which said that peak oil had already happened in 2019 (figure 3a), and depending on the scenario, the 2022 outlook now expects this to happen between 2025 and 2030 (figure 3b). This is due to the stronger-than-expected rebound in economic growth post-COVID-19.

The outlook states that “declines in oil consumption are dominated by the falling use of oil within road transport as the vehicle fleet becomes more efficient and is increasingly electrified.”

The key findings of the 2022 outlook are:

· Apart from the COVID-19-induced dip in 2020, carbon emissions have risen every year since 2015, the year of the Paris Agreement.

· Wind and solar power are expanding rapidly, and this will continue, supported by increasing electrification and low-carbon hydrogen that emerges in the 2030s and 2040s.

· Oil and natural gas continue to play a critical role for decades, but in lower volumes as society reduces its reliance on fossil fuels.

· This implies that natural declines in existing production require continuing investment in new upstream oil and gas over the next 30 years.

· In order to achieve the reduction in carbon emissions implied in the Accelerated and Net-zero scenarios, there must be a significant increase in the pace of investment in renewables that would need to be supported by corresponding investment increases in critical enabling technologies and infrastructure, including transmission and distribution capacity.

· The pace of improvement in energy efficiency over the outlook period – measured by comparing growth in final energy demand and economic activity – is much quicker in all three scenarios than over the past 20 years.

· The energy mix becomes more diverse, with increasing customer choice and growing demands for integration across different fuels and energy services.

Dale warns that, with the global carbon budget running out, “the importance of the world making a decisive shift towards a net-zero future has never been clearer.”

Government ambitions globally have grown markedly in the past few years, pointing to a New Momentum in tackling climate change. But there is significant uncertainty as to how successful countries and regions will be in taking the additional measures required to shift this to Net-zero and closer to the Paris Agreement goals. Achieving those aims and pledges is becoming critical, but with energy security at centre-stage it is by no means certain yet.

Energy security

Europe’s new energy supply strategy aims to ensure energy security while reducing reliance on imports from Russia and as, at the same time, it emerges from the COVID-19 crisis. This appears to have taken priority over economic impact, but also over climate change concerns, bringing with it a great deal of uncertainty, hinging on the unfolding of the war in Ukraine. But it is only a matter of time before energy affordability regains prominence. The remainder of this decade is likely to be defined by how Europe and the world adjust to these fast-evolving forces.

The latest twist to the story is that, in a first for energy imports, the EU is about to ban imports of coal from Russia. This is coupled with the bloc’s decision to reduce Russian natural gas imports by two-thirds this year and eliminate them altogether by 2027, as well as shun Russian oil. The increasing impact of these policies on global energy markets cannot be overstated. The resulting reshuffle in global energy supplies is already proving to be both painful and costly.

With Europe turning to LNG to reduce Russian gas imports, global markets are becoming distorted. As Europe competes with southeast Asia to secure LNG from a tightly-supplied market, prices are going up to the extent that TTF gas futures are set to have an average price of about $25/mn Btu in 2023 and about $15/mn Btu even by 2025 – about four and two-and-a-half times the pre-crisis levels respectively. Such prolonged high gas prices are expected to impact global gas demand over time. They are already denting LNG import demand in India and China. This raises the question: will such gas demand destruction become permanent? The answer is that it really depends on how long this crisis and high prices will last – and how effective the acceleration of energy transition will be.

.png) At the European Gas Conference, held in Vienna between March 21 and 23, the consensus was that the EU will find it hard to phase out Russian gas. There is simply not enough to go around. Should that prove to be correct, and given the plethora of new sanctions and policies that are coming out thick and fast – often without careful consideration of their impact and implications – how will Europe’s energy map look in the future?

At the European Gas Conference, held in Vienna between March 21 and 23, the consensus was that the EU will find it hard to phase out Russian gas. There is simply not enough to go around. Should that prove to be correct, and given the plethora of new sanctions and policies that are coming out thick and fast – often without careful consideration of their impact and implications – how will Europe’s energy map look in the future?

Climate change is not being abandoned, but rather temporarily postponed. The EU and the US have both re-emphasised their determination to accelerate energy transition, weaning themselves off fossil fuels. The EU, in particular, re-confirmed its goal to reduce unabated natural gas consumption by 30% by 2030 and by 80% by 2050. This is vastly more ambitious than even the Net-zero curve in figure 2b – and of course that much more challenging. The US is also promulgating a similar message, albeit more cautiously.

In a recent study, DNV considered the question “By turning its back on Russian oil and gas, will Europe speed up or slow down its transition to cleaner energy?” Its conclusion was that “improved energy security does not come at the cost of decarbonisation and there is likely to be a small acceleration in Europe’s energy transition.” But this depends highly on the extent and duration of the war and permanence, or otherwise, of resulting global geopolitical realignments. DNV also points out that “reduced global trade and cooperation, such as the realignment of global logistics to address a mounting food crisis, and a shortfall of critical minerals, could also slow down the energy transition.”

.png) However, at least in the short to medium-term, evidence shows that many countries – including in the EU - are turning to coal as a quick solution to energy security and price concerns. In addition, with the price of key raw minerals and materials sky-rocketing, and continuing supply chain challenges, growth in new renewable installations appears to be slowing down. Nevertheless, these are considered to be temporary setbacks and that “despite everything, the future looks positive.”

However, at least in the short to medium-term, evidence shows that many countries – including in the EU - are turning to coal as a quick solution to energy security and price concerns. In addition, with the price of key raw minerals and materials sky-rocketing, and continuing supply chain challenges, growth in new renewable installations appears to be slowing down. Nevertheless, these are considered to be temporary setbacks and that “despite everything, the future looks positive.”

But, at least for now, it is not positive enough for Antonio Guterres, UN Secretary General, who attacked governments and financial institutions for a “litany of broken climate promises” when presenting the latest IPCC report. The message from that is “The evidence is clear: the time for action is now. We can halve emissions by 2030.” But amidst the post-COVID-19 and Ukraine war crises will that be heard? Not clear. Maybe later.

What is clear though is that the war in Ukraine has set in motion far-reaching changes that will permanently reshape the global energy and economy scene. How far these will go should become clearer in an updated outlook, promised by Dale in his introduction. He said “We will update the scenario as the possible impacts become clearer.” It will be interesting to see.

The Figures were sourced from BP’s:

and