Boom! LNG spot prices rocket to record levels [LNG Condensed]

The weather, as ever, plays a huge role in gas demand and, after a miserable year for LNG producers, (and many others) 2020 ended with a huge spike in LNG spot prices, the root cause being the northern hemisphere winter, bringing into question the existence and longevity of the global LNG glut.

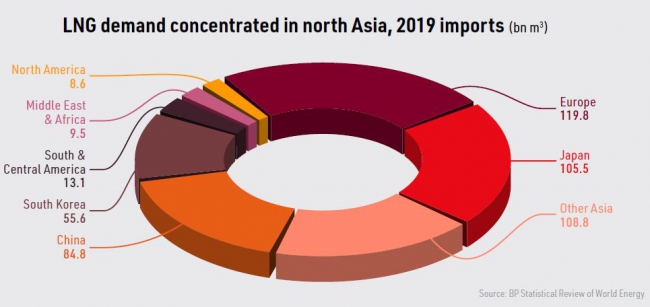

China’s emergence as an LNG importer to rival Japan has been the main driver of LNG market growth over the last decade, but it not just China’s size that is important but its location. It added another major importer in north Asia, alongside Japan and South Korea, with the three countries in 2019 accounting for 50.7% of global LNG imports. When it gets cold, they all get cold together.

Beijing recording its coldest temperatures since 1966 in January, while temperatures in Seoul were down at -18.6° C, the lowest in 35 years. China, Japan and South Korea have all been forced to resort to higher coal, fuel oil and gas burn to meet soaring residential heating demand.

Europe accounted for 24.7% of global LNG demand in 2019, which means that when the northern hemisphere winter is severe, three quarters of the global LNG market is affected, turning a rush for spot cargoes into a stampede.

In theory, this should not be a problem in a market with excess supply but, in reality, the surge in demand has exposed weaknesses in the responsiveness of the global LNG supply chain.

Gas storage

The first port of call in a demand emergency is gas in storage not LNG spot cargoes, which take time to arrive, and the cold winter has again revealed a general lack of storage in Asian markets, particularly China, despite its best efforts to build more capacity.

At the end of 2018, according to Cedigaz, China had underground gas storage of 11.7bn m3, with a maximum withdrawal rate of 156mn m3/d, the equivalent of just over 4% of total demand in 2018 of 283bn m3. However, figures vary. Cedigaz says that by March 2019, Chinese sources put working gas capacity at 13-16bn m3.

Government targets were for gas storage capacity to rise to 14.8bn m3 by 2020, followed by an increase to 35bn m3 by 2030. However, even if the upper figure of 16bn m3 is used, China has insufficient storage capacity when compared against a world average of 11% of total consumption and much higher levels of 20% for the largest gas consuming countries such as the US and some countries in Europe.

Beijing has taken steps to improve the situation, decreeing in 2018 that gas suppliers should have storage facilities able to meet at least 10% of contracted sales by 2020, that city gas distributors have storage capacity of 5% of annual supplies and local governments three days cover for consumption in their administrative regions.

Total planned new capacity has been reported at 55.6bn m3, but much of this still has to come on stream, leaving the country exposed to the weather this winter. Chinese gas storage construction has and continues to play a game of catch up with the country’s long-term growth in LNG demand.

Meanwhile, Japan and South Korea’s storage capacities are better but not copious. In any market, broadly the case for marginal storage capacity additions falls as capacity rises – capacity to deal with a 1-in-50 year event will bring fewer rewards than that which deals with a 1-in-30 or 1-in-20 event. As a result, the most severe weather events generally stress storage capacities.

At the end of 2018, Japan had 11.7bn m3 of working underground gas capacity, equal to 10.1% of total consumption of 115.7bn m3 that year, as well as LNG storage. South Korea, the world’s third largest LNG importer, relies predominantly on storage facilities at its seven LNG regasification terminals, i.e. storing gas as LNG rather than regasified gas.

Neither have the option of using electrical interconnectors or transnational gas pipelines as a means of flexibility within their gas and power systems.

LNG supply response

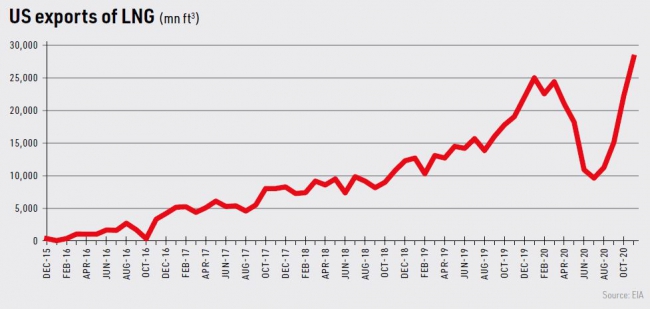

The supply-side of the LNG market was not ready for such an upswing in demand, despite the increases in production capacity of recent years. Low spot prices for LNG in Asia over the summer saw a reduction in feed gas going to US LNG terminals, and a complete cessation temporarily at Sabine Pass and Cameron when hurricane Laura made landfall August 27.

Feed gas to Cameron did not resume until late September, with its first post-hurricane cargo departing October 5. The delay at Cameron was the result of damage to the electrical and marine infrastructure around the facility. Feed gas into Sabine Pass shot up to more than triple summer levels after the hurricane, allowing exports to resume from September 11.

As a side issue, the two plants’ different experiences of the same event highlight that reliance on external electrical supply – increasingly popular as a means of emissions reduction through the supply of power from renewable energy sources – creates a new operational vulnerability. Sabine Pass returned to production quicker because it generates power from gas on site.

However, the number of outages spread further than the US. Production from Train 2 at the 7.8mn mt/yr Gorgon LNG facility in Australia had been idled between July and November 23 after inspections revealed weld quality issues with the train’s propane heat exchanges. Train 1 was also scheduled to go offline from January 2-7.

In addition, shipments from Shell’s troubled 3.6mn mt/yr floating LNG project Prelude were down from February 2020, owing to power problems and only resumed January 12, while Chevron’s Wheatstone LNG plant also saw reduced production as a result of gas supply issues.

Serious safety breaches were found at Norway’s 5.6mn mt/yr Hammerfest LNG plant by the country’s Petroleum Safety Authority following a fire there in September. Operator Equinor warned that the plant was likely to be out of action until October 1, 2021. And, in Algeria, state oil and gas company Sonatrach’s Arzew LNG plant loaded no cargoes in the first half of December.

According to the US Energy Information Administration unplanned outages also occurred in Malaysia, Qatar, Nigeria and Trinidad & Tobago.

Market dynamics

Other factors contributed to the slow market response.

Low LNG spot prices throughout 2020 and continued liquefaction capacity additions meant buyers are likely to have used flexibility clauses to minimise off-take from long-term contracts, increasing their dependence on cheaper spot market purchases.

In addition, while China was the initial epicentre of the Covid-19 pandemic, it has largely brought the virus under control, allowing an earlier economic recovery than most other areas of the world. In the first 11 months of 2020, Chinese LNG demand was up 10.7%, compared with the same period in 2019, to 59.54mn mt. Demand in December surged as a result of the cold weather.

Overall, global LNG demand in 2020 is expected to be roughly the same as 2019, a disappointment for producers in terms of the growth that would have been expected without the pandemic, but hardly the crushing demand blow experienced by the oil market.

However, China’s economic recovery had another effect, which has rebounded on the shipping market. Rising container ship trade, and a spike in LPG cargoes and LNG carriers to meet heightened Asian winter fuel demand have resulted in significant congestion at the Panama Canal. This has been exacerbated by the impact of the pandemic on staff availability to manage canal operations.

According to the Panama Canal Authority, the weather has not helped. The authority has attributed delays to more seasonal fog than usual and hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico. The authority says delays in mid-January were about 5-6 days, down from 10 days in mid-October.

Delays to Panama Canal transits from Covid-19, the weather and increased volumes have all impacted spot cargoes rather than regular traffic with reserved slots and have prompted some shippers to take the longer route around the Cape of Good Hope. But whether vessels stand idle at the canal or make the longer journey, both factors serve to tighten the LNGC market by reducing availability as journey times become extended.

Further exacerbating the problem, as noted by ship brokers Simpson, Spence, Young (SSY) in their 2021 commodity market outlook, is that when Asian LNG premiums rise, LNG cargoes are drawn from the Atlantic basin into the Pacific basin, which in turn also increases journey times and therefore LNGC availability.

In a blogpost December 30, RBN Energy said that it had heard that as many as 10 cargoes have already been cancelled for February 2021 liftings from US terminals, not because of a lack of demand or attractive arbitrage – US domestic gas prices are the lowest in a decade and Asian spot prices at record levels – but because of the inability to book LNGCs.

What now?

The Japan-Korea Marker (JKM) spot price assessment for February hit a record $32.494/mn Btu on January 12, jumping 31% from the previous day, reaching a level way above the price of oil-indexed LNG.

However, it appears to have peaked and prices for March delivery remain much lower and, at the time of writing, had fallen to just below $10/mn Btu, although they could again be driven higher by further cold snaps.

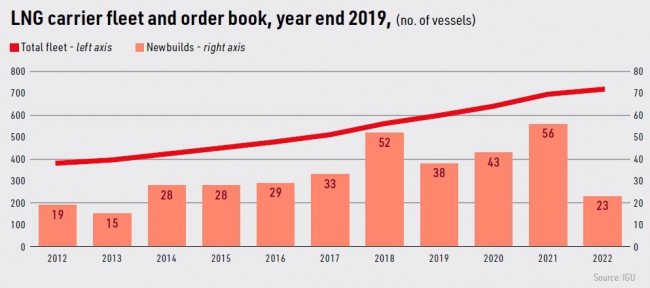

SSY sees a significant amount of newbuild LNGCs coming on to the market at the back end of the first quarter, a process which continues in both the second and third quarters of the year, when ships also come off time charters.

The size of the global LNGC fleet remains on a strong upward trajectory, with about 48 new builds being delivered in 2021 and just over 30 in 2022, according to SSY data, alleviating tanker shortages. As a result, SSY sees a very bearish market for LNGCs in the second and third quarters.

Nonetheless, prices for spot LNG are likely to remain stronger than last year, owing to the lagged effect of restocking in Asian markets. Just as a warm winter adds to price weakness in the summer months, due to limited storage restocking demand, a cold winter provides additional price support as tanks are refilled.

Market tightening?

However, much depends on the expected rebound in demand as economies recover from the pandemic. The start of mass vaccination programmes is clearly positive, but many European countries and the US started the year experiencing the highest death tolls yet from Covid-19 and a new round of lockdowns which will adversely affect their economies and retard any recovery in gas demand.

The prospects in Asia remain brighter, owing to strong policy support for gas in China and India and the continued addition of both LNG import capacity and internal gas distribution infrastructure in both countries. In addition, other developing Asian nations will gradually see planned LNG-to-power chains come into being, boosting LNG demand in countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and new markets like Vietnam.

According to the International Energy Agency, global LNG trade will reach 585bn m3 by 2025, up 21% compared with 2019, but this, it said in June last year, is still a rate below LNG production capacity additions, suggesting an oversupplied market still in the process of gradual rebalancing. In turn, this implies a continuation of relatively low prices, but increasing potential for volatility.

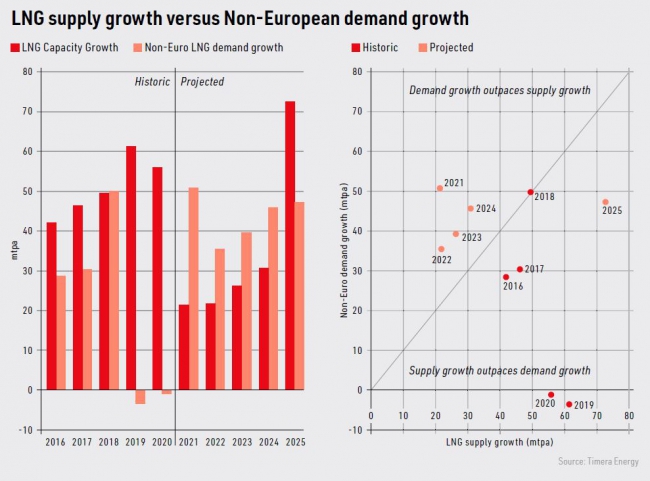

However, risk consultants Timera Energy do see fundamental market tightening significantly over the next four years, as a result of net demand growth. They hold a positive outlook for 2021, owing to pent up demand, economic re-opening post-pandemic and strong fiscal stimuli to get economies back to work.

They project that non-European LNG demand growth will outstrip LNG production growth each year from 2021 to 2024, with the balance changing in 2025, when new Qatari production starts to come on-stream. As a result, they forecast higher absolute price levels than in the period 2016-2020, higher regional price spreads and enhanced volatility with Asia pulling more gas away from Europe.