Back to E&P spending growth [Gas in Transition]

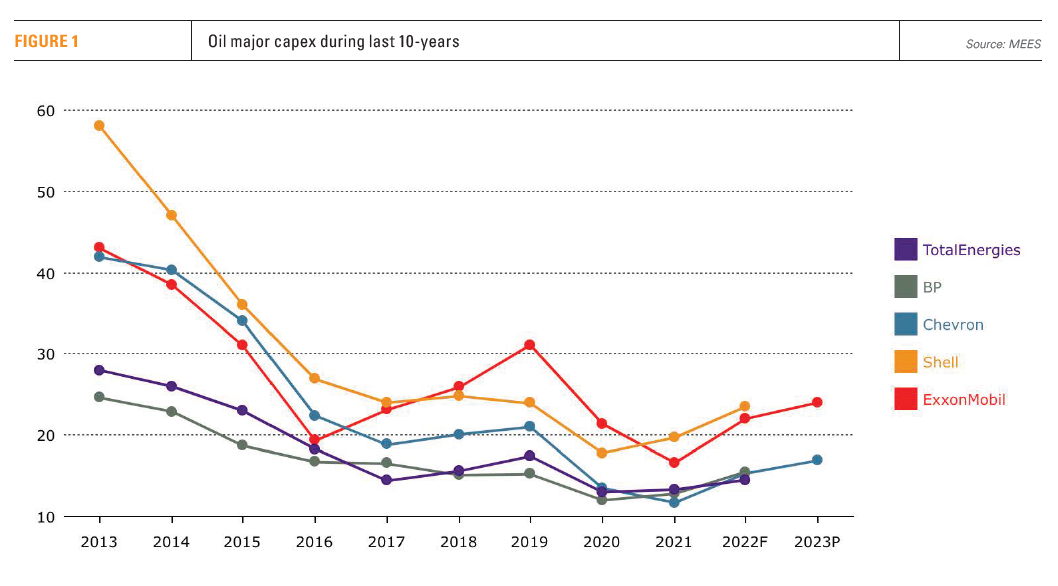

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the net income for the world's oil and natural gas producers is expected to double in 2022 from 2021, to a new high of $4 trillion. The great majority of companies are reporting strong profits. With global oil and gas supplies continuing to be tight, while demand continues to grow, this has emboldened oil and gas companies into increasing E&P spending after years of caution. In fact, in 2022 oil major capex spending was half of the average since 2010 (see figure 1). 2023 will see E&P spending growth.

The outcome of COP27, even though disappointing for not increasing targets for carbon emission cuts, showed that the majority of countries see oil and gas continuing to be important for years to come. Driven by energy security concerns, not only phase-down of oil and gas did not get the required support, but the COP27 deal now includes a provision to boost “low-emissions energy”, interpreted to include natural gas.

Recent energy outlooks, by the IEA, BP, McKinsey and others, based on known policies and trends along which the global energy system is currently progressing, show that the world will still need secure and affordable supplies of oil and gas until 2050. But the drive to achieve energy security while pursuing energy transition poses new challenges.

Years of under-investment have resulted in tight oil and gas supplies globally, low inventory levels, and constrained production levels. The Russian oil price cap and embargo are expected to result in a further reduction in the supply of oil to global markets. With global demand, both for oil and natural gas, expected to carry on increasing in 2023, and beyond, led by China as it emerges from COVID-19, E&P activity can only but increase.

Oil sector

Despite low prices in December, oil price forecasts show a rebound in 2023 to between $92 to $105/barrel, with Bank of America expecting $110/barrel by H2 2023. A recent survey of 38 economists and analysts forecast Brent crude to average close to $94/barrel in 2023. These are substantially above the cost of producing oil, even in the US and Russia, adding to renewed expectations that E&P spending will increase next year.

OPEC is pressing for more upstream investment to support its forecast long-term demand growth. In its recently published World Oil Outlook 2022 report, OPEC expects demand to grow by more than 5mn b/d in the period to 2024, in comparison to 2021, to peak at about 110mn b/d by 2040 and stay at that level until 2045. In order to achieve this, OPEC estimates that “the global oil sector will need cumulative investment of $12.1 trillion in the upstream, midstream and downstream through to 2045.”

Even though OPEC revised 2023 oil demand forecasts mildly down, in response to recessionary pressure, it still expects demand to grow by 1.2mn b/d in 2023 in comparison to 2022, to just under 102mn b/d, exceeding pre-pandemic levels. As a result, without increased investment in oil, the market risks remaining in deficit throughout 2023, something that could push oil prices even higher.

In response to this expected rise in demand, the national oil companies (NOCs) of MENA countries Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Iraq and Kuwait have been increasing spending and expanding their upstream and downstream production capacity, by utilising windfall profits from their 2022 oil and gas exports.

Led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, MENA countries plan to carry on investing in new oil and gas “and will continue to play this role for as long as the world is in need of oil and gas”, as UAE President Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan said during COP27. Saudi Aramco announced plans to expand its crude oil production capacity to 13mn b/d by 2027 and boost gas production by more than 50% by 2030, requiring continuous capex. However, the overarching goal of both the UAE and Saudi Arabia remains transition to green energy.

This is what prompted Wood CEO Ken Kilmartin to say “Middle East’s investments in energy will see the region come to lead the energy transition…their approach is a lesson for the world.” He added that the combination of investments in energy production today, and new technologies for tomorrow, sets the Middle East up to lead the way.

Brazil, the leading deepwater producer, Guyana and Angola are also expected to see increased E&P investments in 2023. Global deepwater oil and gas production is expected to grow by about 60% between 2022 and 2030, to 17mn boe/d (barrels oil equivalent). Over the next decade, deepwater will be where the fastest oil and gas resource growth will take place.

In the US, though, most capex increases next year may be driven by cost increases, running at about 10% to 15%, rather than significant production growth – this is expected to be limited to about 3% to 4%. ExxonMobil announced early December that it will lift capital spending next year by 10% to between $23 billion and $25 billion, with the goal of raising oil and gas production to a record 4.2mn boe/d by the end of 2027. Chevron also said that it expects to spend $14bn in 2023, adding 14% to this year’s budget – enough to cover cost increases and investments in low-carbon business solutions.

Natural gas sector

International oil companies (IOCs) have been shifting their interest and investments to natural gas and LNG in response to surging demand in Europe, to replace Russian gas. But also, in response to increasing demand in Asia. China’s gas demand is forecast to increase by 30% by 2030.

In addition, most available and new LNG has already been contracted. The EU will have to rely on spot-LNG and inevitably high prices over the next few years, especially as gas shortages become apparent next winter. The world needs more gas and LNG.

However, the mixed signals from the European Commission and the US about the longer-term future of natural gas have been acting as a disincentive to increasing IOC investments to pre-pandemic levels. The problem is that nobody knows what the EU's gas demand will be after 2030. This is making it hard for Europe’s utilities to enter into long-term contracts.

A good example of this is that president Joe Biden has been taking measures to cut demand and speed up a shift away from oil and gas, while at the same time his chief energy adviser, Amos Hochstein, described the refusal of US shale investors to ramp up drilling as “un-American,” asking US oil and gas companies to “increase production and seize the moment.” Such mixed messaging discourages the companies from increasing investments into new projects.

As a result, even though 2023 will see growth in natural gas E&P spending, this is expected to be limited in North America – expected to be steady, but not rapid. Despite their very healthy balance sheets, most US oil and gas companies are still sticking to their disciplined spending, developed during the pandemic years, with only modest relaxations. Their new direction is to secure supply in the short term while transitioning to cleaner energy in the long term.

In the East Med, BP and Eni are increasing drilling commitments in Egypt's gas-prolific EEZ, where Chevron has just made a new gas find. ExxonMobil has started exploration south-west of Crete and TotalEnergies is planning drilling in Lebanon’s EEZ. But without readiness by European utilities to commit to long-term gas deals, it is still difficult for IOCs to invest in long-term gas production projects.

At COP27 African countries pressed their case to develop their natural gas resources as part of the energy transition, asking for financial support. They are refusing to sacrifice natural energy assets “to help rich polluters meet emissions targets.” They see a role for gas well into the next decade.

North Sea E&P spending

One area where E&P spending is expected to grow significantly over the next few years is the North Sea.

Companies operating on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS) are benefiting from tax incentives introduced during the pandemic to incentivize upstream activity. With demand increasing, this has contributed to a record-high sanctioning of new projects in 2023.

In the North Sea, Rishi Sunak’s new government has reaffirmed its support for the North Sea oil and gas industry. Earlier in the year he labelled it “the foundation of the UK's energy supply in the decades to come.”

Despite a hefty windfall tax, investment allowances could make it possible for energy companies to regain £0.91 from every pound they invest in the UK. Sunak said: “It’s vital we encourage continued investment by the oil and gas industry in the North Sea and our new investment allowance provides huge tax reliefs for projects that cut emissions.” But he also promised to accelerate energy transition.

The UK has made North Sea E&P a key element of its energy security strategy. Sunak emphasised that when he said “oil and gas are going to be a part of our energy mix in transition for many years to come and it is pie in the sky to pretend otherwise.” This new-found interest in oil and gas is reflected in the increase in greenfield capital expenditures expected to be made on projects on the UK's Continental Shelf (UKCS) in 2023.

It is not a case of bringing prices down, but a case of energy security, of reducing dependence on others for the UK's oil and gas needs, which will remain a significant part of the UK's energy-mix for years to come.

Changing mood

The IEA coined net-zero in 2021 and called a stop in new investments in oil E&P by 2025. This is now proving to have been a dangerous and premature call, the consequences of which have been reduced E&P investments, tight oil and gas supplies and inevitably high prices, with renewables unable to pick-up the shortfall.

Mike Wirth, Chevron CEO, was right when he said “a premature effort to transition from fossil fuels had resulted in unintended consequences,” including energy supply insecurity in crisis-hit Europe and in the US. Despite heavy global investment in renewables in the past 20 years, fossil fuels still meet about 80% of global demand. Governments must hold an “honest conversation about the scale of the energy challenge.” The developed world has been taking affordability and security for granted and that has been found to be wanting.

The green transition is happening but it is not fast enough or reliable enough to respond to rapidly increasing global energy needs. Until that happens, demand for oil and gas, and E&P spending, will continue increasing.

As would be expected, this is attracting criticism that the oil and gas sector is planning expansion that would jeopardise the Paris Agreement. Carbon Tracker warned that “Ultimately, companies are committing tens of billions to projects that are unlikely to break even if governments deliver on their climate pledges, and investors must be aware of the implications.” This completely ignores energy security concerns, focusing solely on climate change.

The world has not yet achieved a satisfactory balance to the energy trilemma: security, affordability and sustainability. The energy crunch has led to a shift in sentiment to energy security. What is needed is the right balance using natural gas as a transition fuel, while investing in renewables and developing green hydrogen and other green technologies until these are able to provide the energy the world needs reliably, affordably and securely. And that favours a return back to increased E&P spending. This is what prompted BlackRock CEO Larry Fink to say “I actually believe we’re going to need hydrocarbons for 70 years.”

Clearly the mood is changing. There is a realisation, driven by energy security concerns, that energy is important in all its forms – including oil and gas – for some time to come. Even capital markets are starting to shift, taking a more pragmatic approach. This was evident at the World Energy Capital Assembly (WECA) that took place in London at the end of November: “Transitions do not happen overnight. The world needs a pragmatic approach to decarbonisation and energy investment, realising the enduring importance of hydrocarbons up to 2050.” Even if Europe and the US continue to differ, as evidenced by the outcome of COP27 this is gaining widespread acceptance among most world governments.