Africa can answer Europe’s call for gas, but in time [Gas in Transition]

A number of African countries are well-positioned to plug a looming supply gap in Europe, given time, as various governments work to scale back its dependence on Russia, the African Energy Chamber (AEC) said in its Q2 2022 Outlook. International oil majors need to ramp up their investment in African energy, though there are recent signals that they are doing just that, the AEC said in its report.

The EU has set a goal of eliminating Russian gas supply, which totalled 155 bcm in pipeline exports last year, as early as 2027. Several member states have turned to Africa as a source of extra supply to replace Russian supply. Africa has delivered on average 18% of European gas imports over the last decade, in the form of pipeline supplies from Algeria and Libya, and LNG shipments mainly from Nigeria and Algeria, but also from Egypt, Angola and Equatorial Guinea.

The fact that Africa is already tied to Europe via pipelines gives it an advantage, the AEC said. Proposed new pipelines connecting south Nigeria with Algeria, namely the onshore Trans Saharan Gas Pipeline (TSGP) and the offshore Nigeria Morocco Gas Pipeline (NMGP), would allow Africa to further extend its reach in the European market. Discussions about both projects have gained traction recently.

Algeria, Niger and Nigeria held talks in late June on reviving the decades-old TSGP plan in late June. They have set up a task force for the project, and have designated an entity to update a feasibility study. The 4,128-km pipeline’s cost has been estimated in the past at $13bn, and it would carry some 30bn m3/year of gas. This would enable Nigeria to tap more of its significant natural and associated gas reserves, assessed by BP at 5.5 trillion m3 proven. The energy ministers of the three countries involved are due to meet again in Algiers at the end of July, to validate the task force’s proposals. NMGP is grander in scope, and would cross over 11 African countries linking Nigeria to Morocco and run to Europe, although it also carries a much larger

The AEC also points to large-scale discoveries off the coasts of Mozambique, Tanzania, Senegal, Mauritania and South Africa as sources of additional gas supply for Europe once developed. All told, the chamber estimates that African gas production could rise from a projected 260bn m3 in 2020 to 470bn m3 under a conservative forecast. It will take until the late 2020s for growth to take off, however, with supply set in the meantime to dip to 240bn m3 by 2025.

Capital outlook

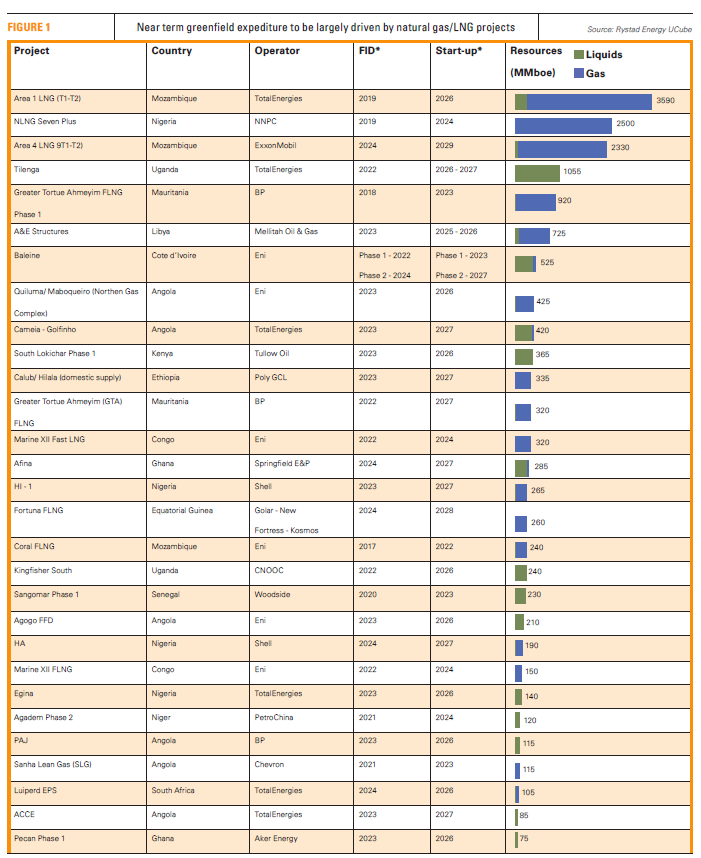

The African oil and gas sector has seen only marginal changes in the capital expenditure outlook over this year so far, the AEC notes, as operators continued to restrain spending in line with post-pandemic and energy transition strategies. However, one noticeable trend has been an increase in greenfield spending and a reduction in brownfield spending.

However, the AEC notes that the recent exodus of international oil companies from Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine is good for Africa. And as they scour the world for alternative investment targets, a number have signalled they want to expand in Africa.

“Even with the number of gas projects being developed or currently delayed, Africa still has significant production potential, if oil and gas operators decide to up the ante on their gas projects on the continent, near and mid-term natural gas production from Africa could surpass the above conservative forecasts,” the AEC said. “Recent signals from oil and gas majors such as BP, Eni, Equinor, Shell and ExxonMobil indicate a shift in strategy towards further investment in Africa,” the AEC said.

Indeed, some are looking at reviving previously shelved projects in response to rising global demand for oil and gas.

BP’s main focus in Africa is several large-scale gas projects in Senegal and Mauritania, namely the Greater Tortue Ahmeyim (GTA), Yakaar-Terenga and BirAllah LNG projects. Supplies from GTA’s 2.5mn metric ton/year first phase have already been sold, and some gas from Yakaar-Terenga’s first phase will be used as feedstock for a gas-to-power plant in Senegal. Gas from GTA’s second phase, Yakaar-Teranga and BirAlla, which could come to a combined 12.5 mt/yr, is all uncontracted and could provide a boost to Europe at a later stage. But these projects are not expected to start up until the late 2020s, though BP is looking at ways of accelerating BirAllah’s development.

Eni is set to bring online the 2.5mn mt/yr Coral FLNG project in Mozambique next year. It is also seeking to tap its African projects in Algeria, Egypt, Angola and Congo-Brazzaville for extra supply for Europe, and recently signed deals to boost gas imports from Algeria and Egypt, as well as agreements with Congo-Brazzaville and Angola.

Equinor, ExxonMobil and Shell all hold significant LNG portfolios in Africa that are yet to be developed. There is ExxonMobil’s 25% stake in Area 4 in Mozambique, although an Islamic insurgency has paralysed investments in the country. The US major might be prompted to finally sanction the Rovuma LNG project in Mozambique, however, in light of its departure from Russia.

Equinor and Shell are inching closer to a $30bn investment in an LNG export project in Tanzania, having signed a framework agreement with the government in mid-June. The project is underpinned by trillions of cubic feet of gas off the country’s coast.

While the pipeline of greenfield projects in Africa is considerable, and largely driven by natural gas and LNG investments, the lead times are long. With the exception of Eni’s Coral FLNG, as well as its Marine XII Fast LNG in Congo, and a seventh NLNG train in Nigeria, they will not benefit the European market until the late 2020s. Africa also needs foreign majors to adjust their strategies to focus more on oil and gas investments in developing markets. International financiers also need to become more willing to invest in oil and gas, in spite of past commitments not to do so, to help Africa develop and provide Europe and other markets with gas that in the next few years will remain in short supply.