A pragmatic energy transition needs natural gas [Gas in Transition]

Energy transition is not an ‘overnight’ process. It will take time. And while it is happening, the world energy needs carry on increasing, along with the need for secure and reliable energy supplies. Low energy, intermittent, renewables are not yet in a position to deliver that.

In Europe, the most energy-intensive sectors are already suffering, with a growing number of companies halting and even permanently shutting down operations. Europe’s major gas-consuming industries — including chemicals, food processing, steel and paper — generate economic value of more than $600bn a year and employ almost 8mn workers. Those areas may be those most at risk.

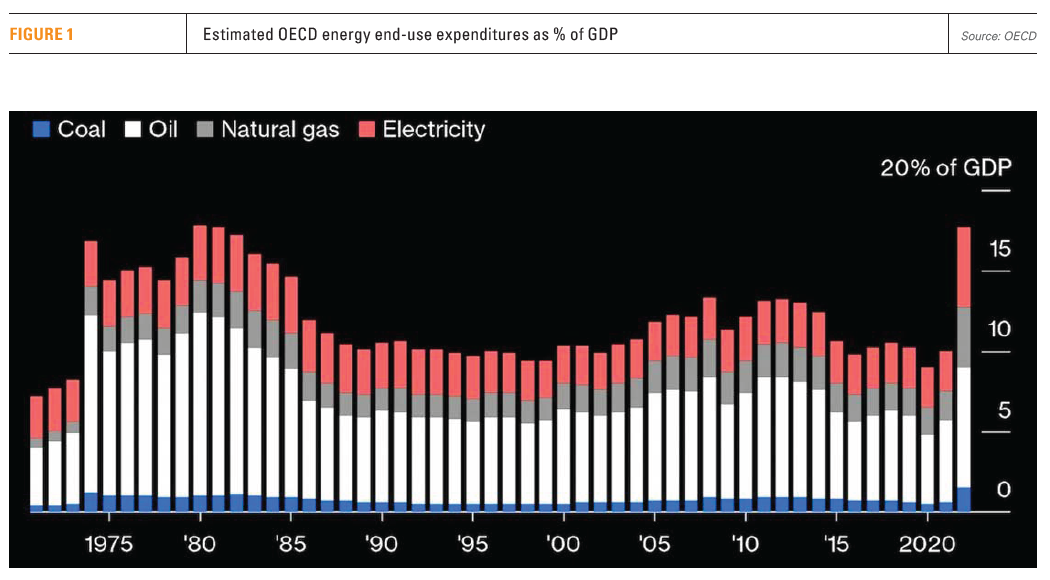

Europe now faces substantially higher fuel import prices in the absence of Russian gas. OECD countries, that include Europe, will be spending 17.7% of their GDP on energy in 2023, about 60% higher than the average of the last 20-years (see figure 1). Clearly, there is a need to find new sources of cheaper energy or risk deindustrialisation. That’s why among many European countries there is increasing wariness that steeper climate ambitions may be counterproductive, given the risks to European industry, but also increased energy costs to consumers.

Repurposing industry, especially heavy industry and chemicals, to low-emission technology will take a long time, and it is unlikely that it will be a panacea. Europe faces strong competitive challenges, with China, the US, Japan and others having access to cheaper energy.

Introducing CBAM will not save Europe. It might go some way in protecting EU businesses from cheaper imports, but competing in global markets will be challenging.

Russia is already redirecting its energy exports to Asia, and in particular to China, at low prices. There are reports that Gazprom is increasing natural gas flows eastward at the request of China. In December these were 16% higher than previously contracted. With a new gas pipeline, Power of Siberia 2, progressing, by 2030 Russia will be exporting more than 100bn m3/yr of gas to China, and even more as LNG, at substantially lower prices than gas costs in Europe at present.

These developments put pressure on Europe to secure new sources of cheaper energy, and in particular cheaper natural gas. An EU policy reversal, recognizing that it will need gas long term can unlock development and export of secure and competitive gas at its doorstep: in the East Med, Middle East and North Africa, around the Caspian and Africa.

Energy security

The energy crisis is forcing governments to reconsider their priorities, with energy security and affordability coming to the top and climate change dropping down the list. It will take a long time before energy security ceases to be a top priority. And not before the problems of reliability and long-term intermittency of renewables are satisfactorily resolved.

In the 1970s coal use was prioritised in order to lower energy costs and this did not change until the 1990s, when the environment and climate change gained importance. In other words, it took over 20 years for the world to shift priorities. The importance of energy security will be with us for a long time to come, alongside dealing with climate change.

As a result of this, the majority of countries at COP27 did not support phasing-down oil and gas and agreed to boost “low-emissions energy”, interpreted to include natural gas. In effect, COP27 signalled a shift from mitigation to adaptation.

In November, Japan announced a change that sheds light on what is going on with global energy and climate change diplomacy. It rebranded its state-owned natural resources company, JOGMEC, which helps local companies to invest in overseas oil, natural gas and mining projects, as the “Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security.” Its purpose? “To contribute to the stable supply of energy and mineral resources to Japan.” It is an important indication of where the priority lies for many nations, particularly in Asia. Energy security is top of the list.

The world is now paying for misguided policies based on committing to a rapid energy transition, mistakenly assuming that sufficient alternatives to oil and gas would already be in place and at scale. That proved to be premature and did not materialise. But it introduced uncertainties about future fossil fuel demand that led to underinvestments in the sector and resulted in tight oil and gas supplies and, inevitably, high prices.

The world is now paying for misguided policies based on committing to a rapid energy transition, mistakenly assuming that sufficient alternatives to oil and gas would already be in place and at scale. That proved to be premature and did not materialise. But it introduced uncertainties about future fossil fuel demand that led to underinvestments in the sector and resulted in tight oil and gas supplies and, inevitably, high prices.

While the world is investing in increasing use of renewables, including green hydrogen, energy efficiency and developing the technologies needed to transition to cleaner energy, a pragmatic energy transition will need natural gas for a long time to come. Unless this is recognized, this may not be the only energy crisis the world will be facing.

BlackRock’s CEO, Larry Fink, recognised this when he said “I actually believe we are going to need hydrocarbons for 70 years.” The company also confirmed earlier in the year that “We expect to remain long-term investors in carbon-intensive companies, because they play crucial roles in the economy and in a successful transition.” BlackRock sees this as a pragmatic commitment alongside investments in decarbonisation.

Climate change impacting renewable energy

Renewable energy resources, which depend on climate, are susceptible to climate change. A report published by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in November concluded that over the past 30-years Europe’s temperature has been rising twice as fast as the global average, impacting its climate. This also results in faster Arctic heating, which in turn may underlie the unusual wind patterns observed in Europe in Q3 2021, characterised by a prolonged period of low wind speeds – as much as 20% lower than the annual average.

As the Arctic gets hotter, the temperature difference with the equator narrows, weakening the jet stream, causing ‘global stilling’ - wind speeds dropping over long periods. In Europe, some of the most pronounced cases of low wind speeds have come over the past decade. With the power generated proportional to the cube of the wind speed near the surface, even small changes can have a significant impact.

Low-speed winds are now becoming a challenge for Europe due its increasing dependence on wind energy. In the summer of 2021 this led to a significant shortfall in power production that had to be provided by natural gas, exacerbating the energy crisis. With the poles warming faster than the equator, this is likely to be a global, recurring, phenomenon.

Climate change is also affecting rainfall, with long periods of drought impacting hydro-electricity and nuclear power, that requires water for cooling.

Dealing with this requires diversification of energy supplies, not just renewables but also natural gas and better storage options, as well as long-term weather forecasting in the energy sector.

Until the problem of long-term intermittency is solved, renewables will need to be supported by natural gas to ensure reliability and security of supplies. Another challenge is that the required technology to store surplus electricity long term, at scale, does not, yet, exist.

Renewables have a long way to go

So far, most effort has concentrated on increasing use of renewables, and reducing or even eliminating use of coal, in the power sector. The use of renewables in other sectors has not progressed as much, particularly in industry – the largest energy user - that consumes more than a third of global final energy demand.

Adding renewable energy to the electrical grid will not solve the climate crisis on its own. Taken together, transportation, industry and heating and cooling make up the lion’s share of energy use and greenhouse gas emissions.

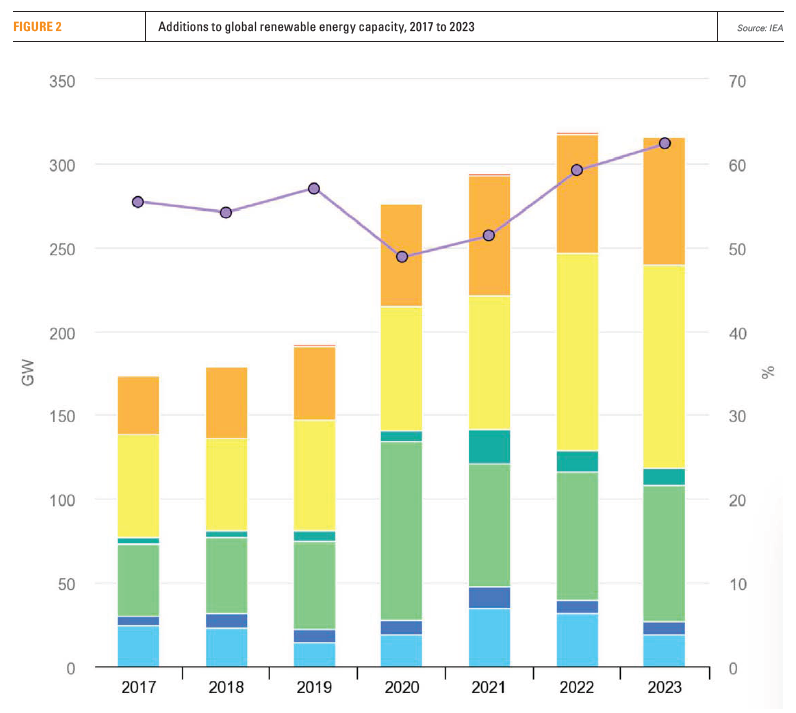

Energy transition is happening but not at the pace required to match growth in overall global energy demand and to achieve transformation within the targeted timescale, ie to achieve net-zero by 2050. And now energy security concerns are acting to delay the process further. According to a new study by McKinsey, getting to net-zero by 2050 will cost an extra $3.5trillion/year investments every year in energy transition. But current investments come to only about a quarter of what is needed. As a result, additions to global renewable energy capacity have stabilised rather than accelerated during the last few years (see figure 2).

Global energy demand will carry on growing. There is a clear link between population growth, economic growth and energy needs. With the world population expected to reach 9.7bn by 2050, from 8bn now, global energy needs will carry on growing. And with Chinese, Indians and other developing countries aspiring to improve their living standards, based on known policies and trends, primary energy demand is expected to increase by close to 20% by 2050.

The global energy crisis that started in late summer 2021 and the war in Ukraine have added momentum to the push to increase renewables. But at the same time the challenges to energy transition are becoming clearer. In addition to the uncertain pace of technological development and deployment, energy security has now become a priority, alongside concerns about economic impacts and, as COP27 showed, lack of consensus about future priorities.

BloombergNEF’s New Energy Outlook 2022 points out that as variable technologies, wind and solar, become highly prevalent in the global power mix, they also create the need for ‘firm-power’ — baseload generators, preferably gas-fired combined with CCS, “that are always available and reliable during periods when wind and solar are less or not available.” Some of that firm-power is needed in short intervals, but, as discussed earlier, some of it could be needed for months, or even longer. BNEF concludes that “Firm-power will not leave the net-zero grid. Far from it.”

A pragmatic energy transition

A report published by the Manhattan Institute in August calls for a reality check to the ‘delusion’ that energy transition will eliminate the use of fossil fuels. It states that “Global economies are facing a potential energy shock…Energy costs and security have returned to centre stage, as has the realisation that the world remains deeply dependent on reliable supplies of petroleum, natural gas, and coal.”

According to the report, the world is beginning to grasp the enormous difficulty of just replacing Russian hydrocarbons, never mind “the impossibility of trying to replace all of society’s use of hydrocarbons with solar, wind, and battery technologies.” And in any case, Russian hydrocarbons are not being replaced, they are being displaced and being used by others. Global demand for oil and natural gas continues to increase as the global economy continues to grow following the pandemic.

The share of fossil fuels in the global energy mix has been stubbornly high, at around 80%, for decades, and it will be so this year. Forecasts based on achieving the goal of net-zero by 2050 are aspirational, goal-setting, rather real. That’s what we all want to see and the world must endeavour to achieve it, while at the same time ensuring secure and affordable supplies for the world’s growing energy needs all the way to 2050. Transition to clean energy is crucial to the world’s future, but many questions remain unresolved.

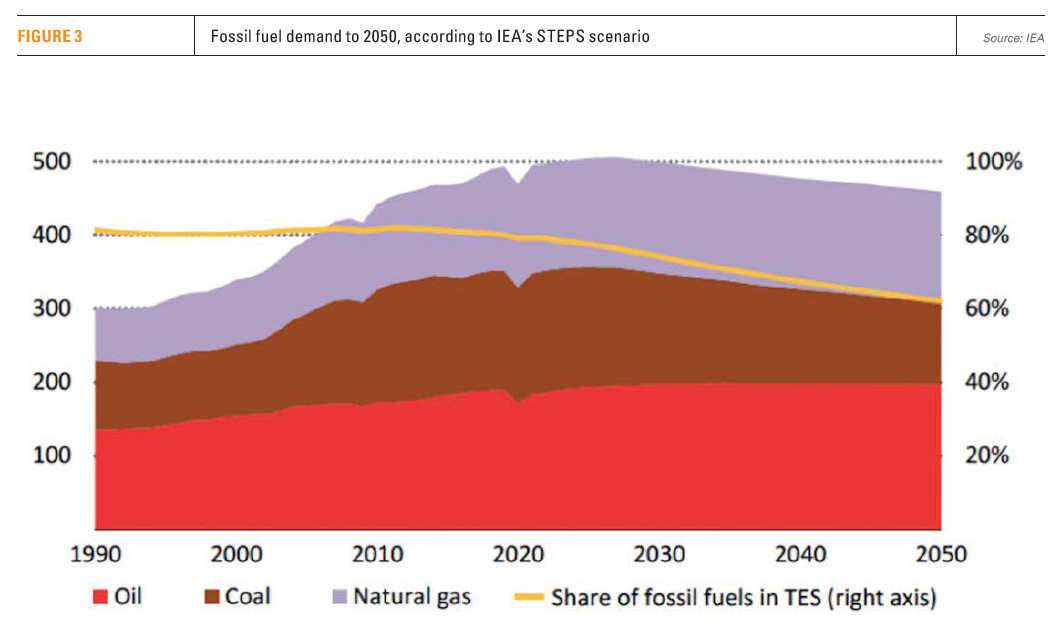

At present and in the foreseeable future reality is different. Even though much of this energy growth is likely to be provided by green energy, based on known policies and trends along which the global energy system is currently progressing (as in IEA’s STEPS scenario), in real terms oil and gas demand will remain close to today’s levels even by 2050, even as coal demand contracts (see figure 3).

This could of course change if the world takes aggressive measures to reduce dependence on oil and gas, but that is still to happen and certainly the current energy and economic crises, and the fact that the required technology and infrastructure is still being developed, are delaying such action.

Unquestionable faith and optimism alone will not make it happen. Assuming that the required technology and infrastructure will be there when needed is not enough. Pushing the world to gamble its future on such faith is more than risky, it is foolhardy. In effect, as Daniel Yergin points out, advocacy is taking precedence over analysis and reality.

Even the International Energy Agency (IEA) concluded in its September 2022 report that “the clean energy economy is gaining ground, but greater efforts are needed now to get on track for net-zero by 2050.” Of the tracked 55 components of the energy system that are critical for clean energy transitions, only “2 are fully on-track with the net-zero-by-2050 scenario trajectory.” In addition, the procurement of raw materials and critical minerals needed for green energy systems is also facing major challenges, still to be addressed. As Siemens Energy’s CEO, Christian Bruch, said “the transformation we need to go through is complex and massive. We can see that the elements we’re driving today aren’t sufficient.”

There is now recognition that energy transition needs to be based on energy security, i.e. adequate and reasonably priced energy supplies, to ensure public and political support. The two must go hand-in-hand.

That is why the world needs a pragmatic energy transition, that recognizes that until the required green technology is available and adequate, natural gas will remain a key part of the global energy mix – all the way to 2050.