BP foresees faster transition away from oil, gas [Gas in Transition]

BP made a bold shift in its Energy Outlook 2023, published at the end of January. It states that the upheaval caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will push countries to pursue greater energy security over the next decade, with oil and gas consumption declining faster than it predicted previously, while accelerating the shift towards a more local energy mix and renewable energy. BP expects that, as a result, global CO2 emissions will decline at a faster rate.

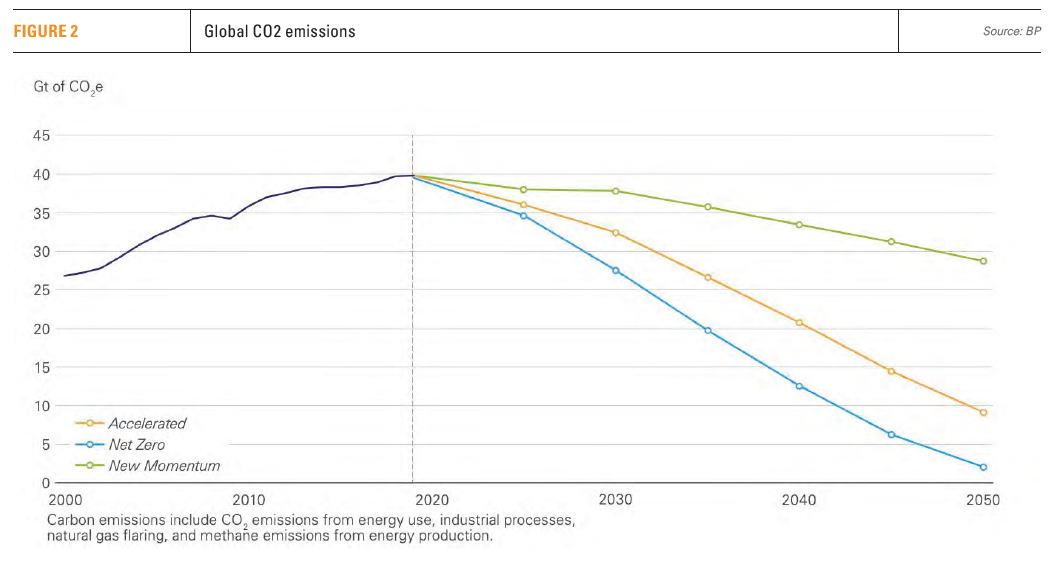

BP maps out three scenarios, chosen to explore the uncertainties surrounding the speed and shape of the energy transition to 2050. “Accelerated” and “Net Zero” are broadly in line with Paris-consistent IPCC scenarios. They have been designed to achieve substantial reductions in CO2 emissions by 2050, by around 75% in Accelerated and over 95% in Net Zero, that also includes a shift in societal behaviour and preferences to further support gains in energy efficiency and the adoption of low-carbon energy. In other words, they are scenarios designed to produce a predetermined outcome.

“New Momentum” is designed to capture the broad trajectory along which the global energy system is currently travelling. As such, it is nearer being a projection based on current trends and known policies, by placing weight “on the marked increase in global ambition for decarbonization in recent years, as well as on the manner and speed of decarbonization seen over the recent past.”

BP warns that “the scenarios are not predictions of what is likely to happen or what BP would like to happen.” In fact, it states that “the many uncertainties surrounding the transition of the global energy system mean that the probability of any one of these scenarios materialising exactly as described is negligible.” Nevertheless, the Outlook provides a useful guide on what may happen to the global energy system between now and 2050.

BP identified a number of trends common to all scenarios:

- The global carbon budget is running out. Despite all measures taken so far and government policies, CO2 emissions have increased every year since the Paris COP in 2015, except in 2020.

- The Russia-Ukraine war is having long-lasting effects on the global energy system and is helping to accelerate the energy transition.

- The structure of energy demand changes, with the importance of fossil fuels declining, replaced by a growing share of renewable energy and by increasing electrification.

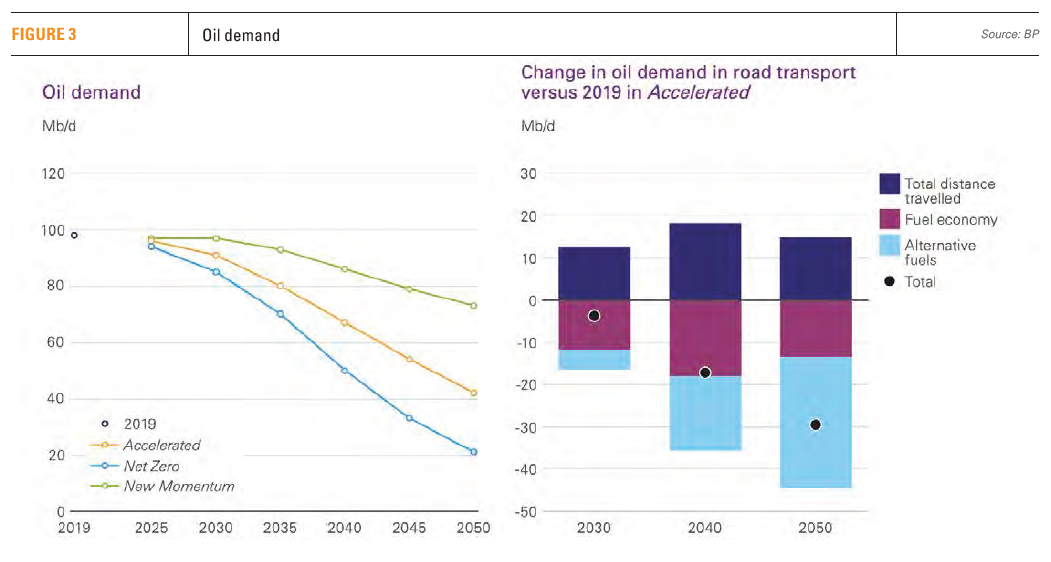

- Oil demand declines over the outlook, driven by falling use in road transport as the efficiency of the vehicle fleet improves and the electrification of road vehicles accelerates.

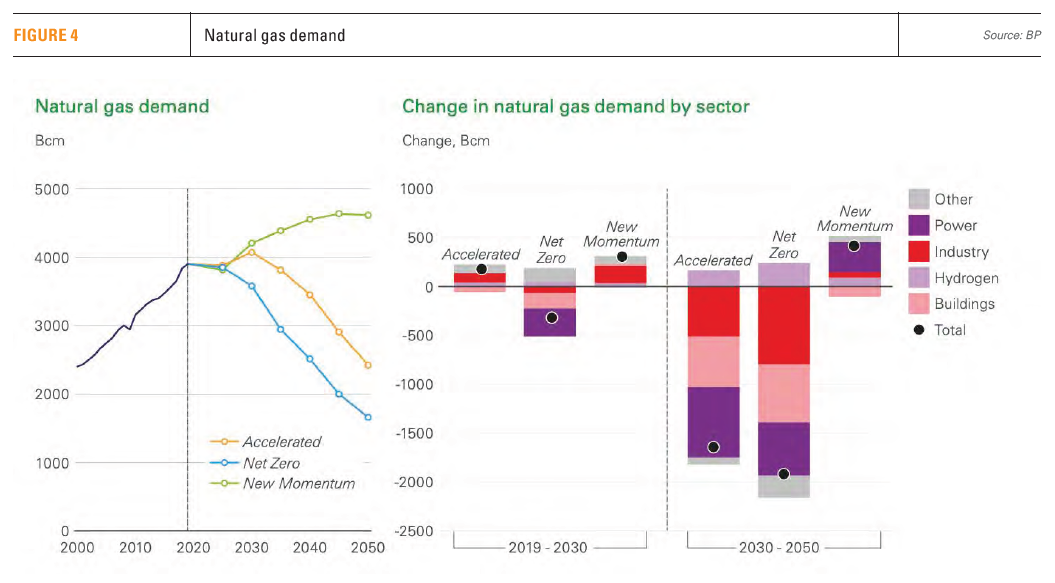

- The prospects for natural gas depend on the speed of the energy transition, with increasing demand in emerging economies as they grow and industrialise offset by the transition to lower carbon energy sources, led by the developed world.

- The recent energy shortages and price spikes highlight the importance of the transition away from hydrocarbons being orderly, such that the demand for hydrocarbons falls in line with available supplies.

- Natural declines in existing production sources mean there needs to be continuing upstream investment in oil and natural gas over the next 30 years.

- The global power system decarbonises, led by the increasing dominance of wind and solar power.

- Low-carbon hydrogen plays a critical role in decarbonizing the energy system, especially in hard- to-abate processes and activities in industry and transport.

- Carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) plays a central role in enabling rapid decarbonisation.

In his introduction to the Outlook, Spencer Dale, BP’s chief economist, states that “the desire of countries to bolster their energy security by reducing their dependency on imported energy – dominated by fossil fuels – and instead have access to more domestically produced energy – much of which is likely to come from renewables and other non- fossil energy sources – suggests that the war is likely to accelerate the pace of the energy transition.”

.png)

The continuing rise in carbon emissions and the increasing frequency of extreme weather events in recent years highlight more clearly than ever the importance of a decisive shift towards a net-zero future, while also addressing all three dimensions of the energy trilemma: security, affordability, sustainability.

But Date cautions that “any successful and enduring energy transition needs to address all three elements of the trilemma.”

Final energy demand and emissions

In a break with previous outlooks, BP now finds that final energy demand peaks in all three scenarios, including New Momentum, as gains in energy efficiency accelerate (see figure 1).

This is dominated by four trends: declining role for hydrocarbons, rapid expansion in renewables, increasing electrification, and growing use of low-carbon hydrogen that plays an important role in helping the energy system to decarbonize. Not surprisingly, these trends also impact carbon emissions (see figure 2).

Total final consumption decarbonises as the direct use of fossil fuels declines, the world electrifies and the power sector is increasingly decarbonised. But despite this, under the New Momentum scenario, which better reflects current policies, the world is still far behind achieving net zero emissions by 2050. According to this, by 2050 global carbon emissions will only be about 30% below 2019 levels.

Increasing use of CCUS also plays a central role in enabling deep decarbonization. The outlook considers this necessary to achieve the Paris climate goals.

The role of electricity increases substantially and broadly uniformly across all three scenarios, with electricity consumption increasing by around 75% by 2050.

Oil and natural gas

The outlook indicates that oil demand will fall over the period to 2050 as use in road transportation declines and as the world switches to lower-carbon alternatives (see figure 3).

According to the New Momentum scenario, that better reflects the trajectory the world is going, global oil demand plateaus at about 100mn barrels/day over the next 10 years and then declines gradually to about 75mn b/d by 2050.

The prospects for natural gas depend on the speed of the energy transition, with demand under the New Momentum rising throughout the period to 2050 by as much as 20% above 2019 levels (see figure 4).

The range of the differences in global gas demand in 2050 across the three scenarios, relative to current levels, highlights the sensitivity of natural gas, and LNG, to the speed and form of the energy transition.

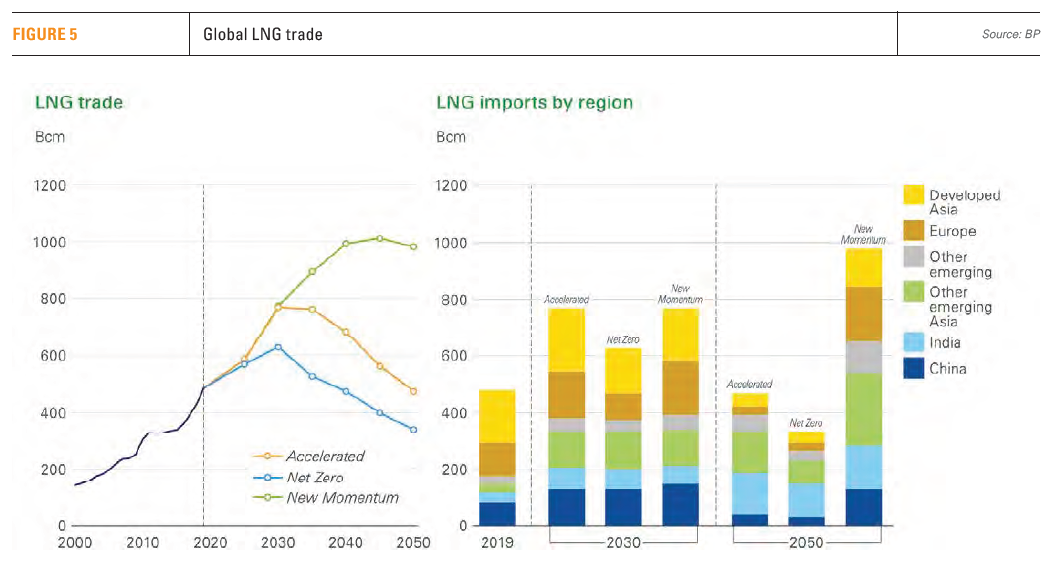

LNG trade increases in the near term, with the outlook becoming more uncertain after 2030. Much of this growth is driven by increasing gas demand in emerging Asia where power generation is expected to grow rapidly, as these countries switch away from coal and, outside of China, continue to industrialise (see figure 5).

According to the New Momentum scenario, by 2040 the LNG market is expected to nearly double its 2019 level, with production dominated by the US and the Middle East.

Renewables and electricity

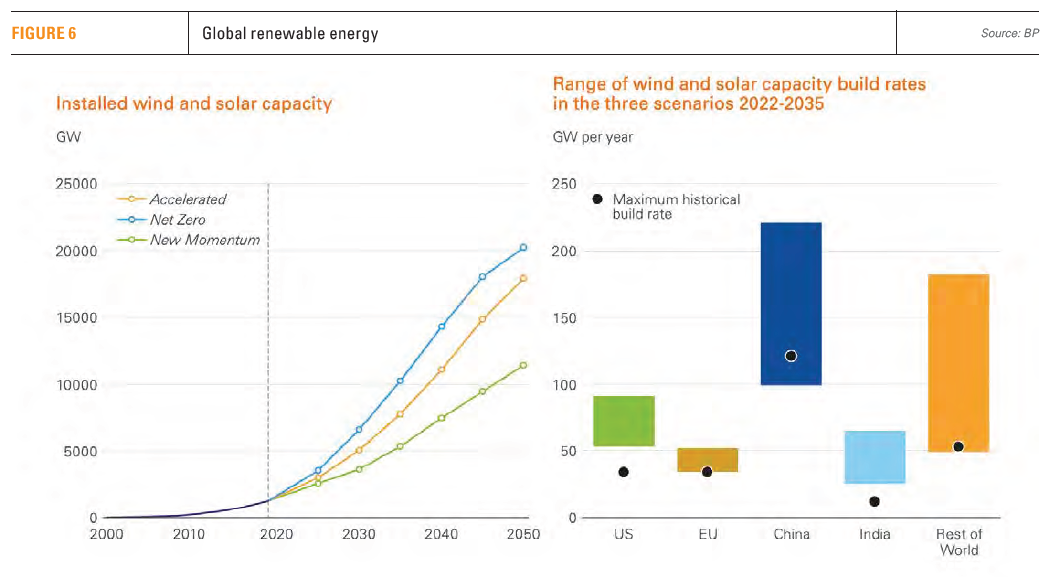

Wind and solar power are expected to expand rapidly (see figure 6), but that will require significant acceleration in financing and building of new capacity. Even under New Momentum, wind and solar installed capacities are expected to increase by around nine-fold over the period to 2050, driven by falls in their costs.

Under the Accelerated and Net Zero scenarios around a quarter to a third of the capacity is expected to be used to produce green hydrogen by 2050.

The growth in installed wind and solar capacity up to 2035 will be dominated by China and the developed world, each of which will account for 30% to 40% of the overall increase in capacity in all three scenarios.

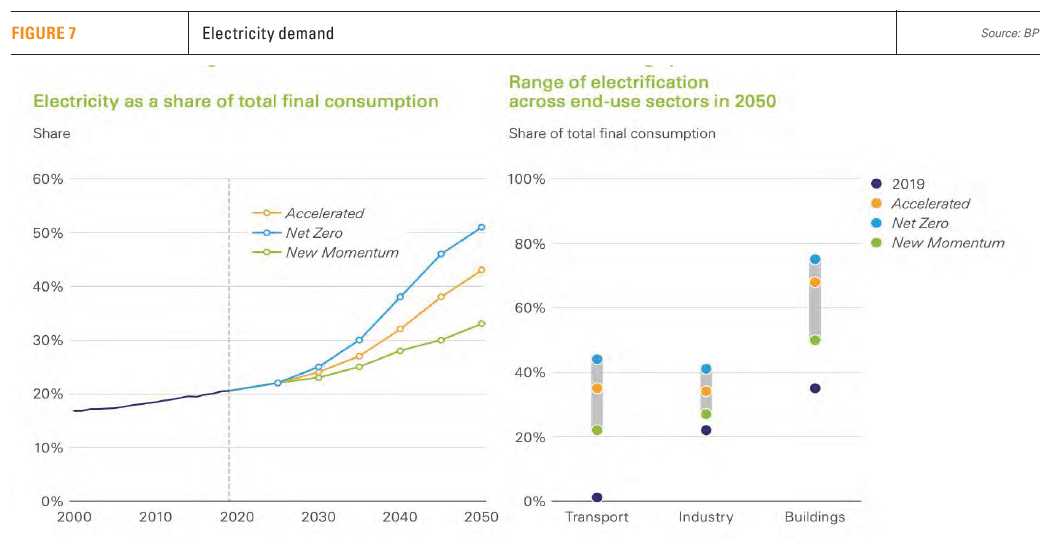

Electricity demand expands significantly as prosperity in emerging economies grows and the world increasingly electrifies, but the mix of power generation differs between developed and emerging economies (see figure 7).

Final electricity demand increases by around 75% by 2050 in all three scenarios.

The increase in electrification is apparent across all-end-use sectors. The greatest scope for electrification is in buildings, where at least half of final energy demand is electrified by 2050 in all three scenarios.

Increasing use of solar and wind, which accounts for all or most of the increase in power generation over the outlook, helps decarbonise the global power system. The expected massive increase in renewables means that governments will need to invest in modernising electricity grids and in storage capacity.

Investment and critical minerals

Investment in wind and solar capacity increases sharply, but it also continues in upstream oil and natural gas production throughout the Outlook period despite declining levels of demand.

Although the demand for oil and gas falls in all three scenarios, natural base decline in existing production means that continuing investment in upstream oil and natural gas assets is required in all three scenarios to meet future demand.

Energy transition leads to a significant increase in the demand for critical minerals critical for the infrastructure and equipment supporting transition. This requires a significant increase in investment and resources within the critical minerals mining sector, as well as ensuring close scrutiny on the sustainability of new and existing mining activity.

Challenges

BP’s outlook projects faster oil and gas decline as adoption of clean energy increases. Based on the outlook, an optimistic headline boldly stated “sustainable energy flourishes as fossils fade.” But is this actually happening?

Even BP sounds unsure. Dale states that “the scale of the economic and social disruptions over the past year associated with the loss of just a fraction of the world’s fossil fuels has also highlighted the need for the transition away from hydrocarbons to be orderly, such that the demand for hydrocarbons falls in line with available supplies, avoiding future periods of energy shortages and higher prices.” This is a key recommendation that must be heeded by those advocating an immediate stop to further hydrocarbon E&P. As Dale points out, “the events of the past year have served as a reminder to us all that this transition also needs to take account of the security and affordability of energy.”

BP also points out that even though government support for the energy transition has increased, the scale of the decarbonisation challenge – emissions are still increasing – suggests greater support is required, including policies to facilitate quicker permitting and approval of low-carbon energy and infrastructure. Clearly, we still have a long way to go to get there.

Bloomberg also warned that there is still a lot more ground to cover. “In order to get on track for net zero emissions in 2050, the world would need to immediately triple the $1.1 trillion spent [on renewables in 2022] and add hundreds of billions of dollars more for the global power grid.” In fact, according to International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates, this year net renewable capacity additions will remain at the same level as in 2022, and not much higher than in 2020 and 2021.

The reality is that global energy transition will take time. In order to achieve the optimistically rapid transition envisioned by the Accelerated and Net Zero scenarios, the world will need a step change investment in renewable and low-emissions technologies, while maintaining investment in oil and natural gas over the next 30 years,

Global energy demand actually carries on growing as world population increases and as emerging economies aspire to improve their living standards and, as a result, despite the rapid increase in renewables to meet this, the world will also require oil and gas for some time to come – as the more realistic New Momentum scenario indicates.

In addition, growing populations and rising GDP and prosperity are also boosting demand for petrochemicals and plastics. This is driving global oil and gas demand and it is expected to largely offset any reductions due to the transition away from fossil fuels in transport. BNEF estimates that by 2050 20% of global oil demand will go into the production of petrochemicals.

Even the IEA’s Future of Petrochemicals report in 2018 identified petrochemicals as the sector rapidly becoming the largest driver of global oil demand.

Global energy trade routes changed dramatically following the war, particularly after Russia halted most of its natural gas exports to Europe, and Europe banned imports of Russian oil. BP expects that energy security concerns caused by the war will reduce the role of oil and gas imports. But while that may be the aim in Europe, it is still not necessarily the case for the rest of the world, particularly Asia. Nevertheless, as Dale pointed out “the events of the past year have highlighted the complexity and interconnectedness of the global energy system.” The full impact of this is still unravelling.

It is likely that the world will experience more energy crises along the way, especially if the shift away from oil and gas is accelerated too soon, before renewables reach the required levels to provide the energy the world will need reliably. Intermittency is still a problem.

BloombergNEF’s (BNEF) New Energy Outlook 2022 points out that as variable technologies, wind and solar, become highly prevalent in the global power mix, they also create the need for baseload supplies, preferably gas-fired combined with CCUS, “that are always available and reliable during periods when wind and solar are less or not available.” Some of that firm-power is needed in short intervals, but some of it could be needed for months, or even longer. BNEF concludes that “Firm-power will not leave the net-zero grid. Far from it.”

BP appears to agree. It warned that the world risks energy price swings and shortages unless there is continued investment in the oil and gas sector over the next three decades.

A recent Bloomberg article states “A BP model [Net Zero scenario] envisions [oil] demand plummeting almost 80% by mid-century, but the steps to getting there appear increasingly outlandish.” These models look increasingly farfetched.

According to BP, global oil demand has already peaked. Even under its most realistic scenario, New Momentum, assumes that peak oil has already happened and expects demand to carry on falling. It is not the first time BP has made the peak-oil call. But this does not reflect reality. Oil demand increased in 2022 and all other forecasts expect it to do so in 2023 and likely beyond. In fact, The IEA has projected that oil demand this year will grow by nearly 2mn b/d, reaching 101.7mn b/d.

Net zero models look increasingly at odds with short to medium-term trends. It does not look possible that oil demand will “plummet in a matter of months and keep falling precipitously every year for the next decade.”

As BP points out in the outlook, rapid acceleration in the deployment of wind and solar capacity still depends on a number of enabling factors scaling at a corresponding pace, including the expansion of transmission and distribution capacity, and development of market frameworks to manage intermittency. Until these are addressed satisfactorily, all energy sources will be needed.

That is, perhaps, one of the reasons that prompted Bernard Looney, chief executive of BP, to say that he wants to "dial back" on the company's green energy push, concerned about the lower returns from its investments in renewables, and stick with oil and gas investments longer, after record profits in 2022. In a strategy update, BP said it plans to curb oil and gas output by 25% by 2030 compared to 2019, significantly down from the 40% cut pledged in 2020. It is also increasing oil and gas investments by $8bn by 2030 in order to “meet near-term demand.”

BP is clearly becoming mindful that while it is investing in renewables, it does not run down oil and gas too aggressively, especially as world focus has now shifted more to energy security rather than just climate change.

Even US president Joe Biden went off script in his State of the Union speech in February when he said that the US would need oil for “at least another decade”.

Net Zero also assumes a shift in societal behaviour and preferences to further support gains in energy efficiency and the adoption of low-carbon energy – not born by reality so far. Innovation is the only way to solve climate change long-term, rather than relying on social behavioural change.

Recent events also show how relatively small disruptions to energy supplies can lead to severe economic and social costs, highlighting the importance that the transition away from hydrocarbons is orderly, such that the demand for hydrocarbons falls in line with actually available alternative energy supplies, something that will take time.

All signs point to a long-term energy shift. It is a transition, not a step change.

Undoubtedly there is momentum behind clean energy, especially as a reaction to the war, but it does not yet follow that, in global terms, oil and gas are fading. At least this is not borne out by the New Momentum scenario, which is more realistic in the short to medium-term - “designed to capture the broad trajectory along which the global energy system is currently travelling.”

Only the Accelerated and Net Zero scenarios show oil and gas fading, but these were designed by BP to produce a predetermined outcome. They offer possible trajectories – aspirations – to lower emissions, but there are no indications yet that the global energy system is following these trajectories. It will take a major shift in policies, technology and investments to do so. Until that happens, the world will need balanced, secure and reliable energy supplies – including oil and natural gas.