[NGW Magazine] Balkan Pride and Pipelines

The Balkans are living up to their reputation, with divisive rivalries leading to competing infrastructure projects, even though – until more is known about Romanian reserves – Russia is the only option for near-term deliveries of large volumes.

After the recent parliamentary elections in Hungary, many commentators believe that Viktor Orban will foster efforts to diversify gas supply, as he suggested during the election campaign, primarily from Romania. But these may be only pre-election promises and contain an element of negotiation with Russia’s Gazprom, as Hungary seeks to extend the gas supply contract and build TurkStream.

This ambiguity regarding Hungary's gas choices is symptomatic of the situation of central and southeast Europe (CE/SEE) as a whole. For over two decades the region has been torn two ways and has been the slowest to integrate itself into the EU. It is heavily dependent on Russian gas and transit through Ukraine and so it is tempted by the possibility of benefits to come from sharing in new Russian pipeline projects.

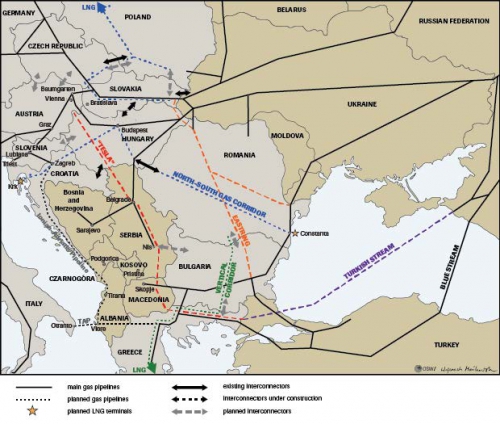

The other choice is EU-supported diversification plans. First it was Nabucco against Russia's South Stream; now it is the Southern Gas Corridor and LNG against Russia's TurkStream. Over these two decades it has been difficult to judge which way CE/SEE will jump. Is there a third way between Russian and EU machinations? Russian claims about halting gas transit through Ukraine by the end of 2019 seem more realistic as Gazprom has repudiated the Stockholm arbitration court award on the transit contract. That decision amplifies the risk of gas supply problems in the near future and so the need for CE/SEE to prepare strategic decisions.

EU way: diversification and integration

The dependence of CE/SEE on Russian gas supplies and its vulnerability to supply interruptions lies at the heart of EU's activities in the region. Finding more sources of supply in CE/SEE has been defined as one of the objectives of the Energy Security Strategy that has been developed within the Energy Union framework.

At the beginning of his term the European Commission's vice-president for the Energy Union Maros Sefcovic spoke about the goal of ensuring three independent sources of gas to every country of the region. The Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) has for years been the flagship EU diversification project in the region. Unfinished despite decades of support, with less than the originally planned capacity and controlled by the autocratic governments of Azerbaijan and Turkey, the SGC raises questions about the effectiveness of EU actions. Nevertheless, it is ready to start up. Commercial supplies of Azeri gas through the TransAnatolian Pipeline and the TransAdriatic Pipeline to southern and south-eastern Europe are expected to start in March 2020. Although not that significant in the scale of the whole EU, the SGC can make a difference in the CE/SEE, though the real impact of SGC on the regional markets is still to be seen.

The EU also supports the development of LNG terminals in CE/SEE – in Croatia and in Greece. Brussels’ efforts in this regard enjoy the political support of the US administration. But even so, and despite the growing availability of LNG, neither project is certain, with the still-awaited final investment decision for the terminal in Krk; and the even vaguer prospects of realisation of FSRU in Alexandroupolis in northeast Greece.

More successful seems to be the EU support for regional integration, recently realised mostly in the framework of the Central and South East Europe Energy Connectivity (Cesec), which was set up in 2015. Although many interconnection projects are still being built, some are missing reverse flow; and many have not been realised at all. Despite that it is possible to discern growing interconnectivity and new options for north-south, south-north and west-east flows in CE/SEE, the latter being mostly due to Ukraine.

Connections are in place between Slovakia and Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria and Hungary and Romania and bi-directional flows have gradually been enabled on most of the existing pipelines in the region. The key link between Bulgaria and Greece should be realised next year. The recent list of projects of common interest includes a Bulgaria-Serbia interconnector, or elements of the Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria (BRUA) project. Physical interconnectivity has been supported by the push for implementation of EU rules. Transparency and access to information – including about gas flow through Romania – or the application of provisions to decades-old infrastructure – including third-party access to the Trans-Balkan gas pipeline and the European Union system of network codes – are, at least in theory, aimed to facilitate the entry of new actors on the regional market and increase supply options.

Russia divides and conquers

The limited effectiveness of EU diversification activities in the region clearly suits Russian interests. For Gazprom CE/SEE is important, less as a market for its gas than as a kind of gateway for pipeline supplies to Italy – one of the largest EU markets – and the Central European Gas Hub at Baumgarten, Austria.

So its actions are aimed not only at maintaining market share, but also at controlling and influencing gas routes including blocking diversification options, as has been shown by EC antitrust proceedings. This explains the reluctance to renegotiate transit contracts in the trans-Balkan gas pipelines and its subsequent projects to create an alternative to the Ukrainian, southern supply corridor to the Balkans and via the Balkans to Italy and Austria.

Gazprom is learning from its own mistakes and adapting to the changing situation in the region and the EU. So the key role in TurkStream is being played by Turkey, which is outside the EU market and its regulations. For TurkStream’s onshore legs, despite new projects popping up such as Tesla or Serbian Stream, Gazprom would probably try to use existing infrastructure such as the Trans-Balkan gas pipeline or those built and planned with EU money such as the Bulgarian and Serbian interconnections, TAP, and ITGI Poseidon.

There are reports that Gazprom or related companies are actively participating in open seasons for new or existing capacity in key interconnectors in the region, including those announced by the Bulgarian and/or Serbian TSOs.

This strategy should enable it to economise on both money and time, react to the changing market situation and also limit the capacity available for gas supplies from alternative sources. At the same time, Gazprom, which has not yet specified the exact onshore route of TurkStream, is using its traditional tactics of playing off rival interests against each other. After all this is a region where practically every country wants to at least hold on to, if not increase, its transit role and if possible become a regionally significant hub.

Regional way?

Although CE/SEE countries have faced common challenges for years, and jointly participated in Russian projects as well as the EU policy framework, defining common interests and a common gas market is still difficult for the region as a whole, which simplifies Gazprom’s task.

Proposals of new gas supply routes in central and south-eastern Europe (Credit: OSW)

The countries are separate and divided, culturally and politically and in terms of their natural resource endowments or energy mixes. Romania is one of the few gas producers in the EU with the possibility of much expanding its production – up to 20bn m³/yr from 2025. Despite this, for years the reverse flow and gas supply via the Romania-Hungary link has not been possible and Romanian-Bulgarian gas relations also happen to be problematic. Croatia, also a gas producer, is one of the most independent countries where Russia is concerned, and for years it has been trying to implement projects enabling alternative supplies to the region, including the LNG terminal in Krk and the Ionian Adriatic Pipeline.

At the same time, however, there are still problems with reverse flows on the Croatia - Hungary interconnector, although a memorandum of understanding signed last year may help to solve them. Croatian-Serbian relations are also complicated. And Serbia and Bulgaria remain strongly isolated and are the most dependent on supplies from Russia through Ukraine. If their gas security were to improve significantly, that would be positive proof that Sofia, Belgrade and Brussels had done a thorough job.

Competing projects reflect national differences

The ebb and flow of these bilateral relations, characterised by animosity rather than co-operation, is reflected in the multiplicity of gas pipeline projects that the region generates and in the general uncertainty about which will succeed. Slovakia, wanting to maintain its transit role, has been promoting the Eastring project for several years, which would run from Romania or Bulgaria through Hungary to Slovakia where it would be connected to the existing infrastructure running to the west of the EU. However, it still remains at the memorandum of understanding stage with some regional pipeline operators.

The BRUA project remains of strategic importance for Romania and seems to have gained momentum, owing to the prospects of more gas from Romania’s Black Sea. However, its final shape is not obvious either. It is not known whether it will start in Bulgaria or only in Romania (becoming ROHUAT), if indeed it runs to Austria, or if it will instead terminate in Hungary (becoming ROHU).

Bulgaria is trying to finally diversify routes and sources of supply, including pushing forward the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria and the Alexandroupolis LNG terminal, planned together with Greece. At the same time, it seems to be equally interested in participating in TurkStream, which may result in Russian gas flowing through the newly built interconnectors.

Not only does each CE/SEE state have aspirations to become an important regional gas hub: but Turkey and Ukraine, outside the EU also have ambitions. The Ukrainian pipeline operator just recently announced an analysis of the market demand for capacity from Romania to Ukraine.

Summary

- Different endowments, interests and animosities between CE/SEE states underline the importance of the existing frameworks for regular debate by market participants or politicians on common gas related goals and projects (such as Cesec or the Energy Community). The probability of the all but total halt of Russian gas transit through Ukraine after 2019 may mobilise and facilitate political decisions and sift out unrealistic projects.

- Gradual market integration and development of interconnectors in CE/SEE don’t have to mean diversification of gas supply sources. Interconnectivity reinforced by implementation and enforcement of EU rules such as those on third party access and transparency in various gas market segments may be key for ensuring security of supply in in EU and non-EU countries of the region and limit the scope for market abuse. At the same time the prospects for substantial growth of gas production in the region and its immediate vicinity (the Romanian shelf, EastMed) may widen the menu of sources.

- The role of gas remains relatively small in many CE/SEE states, especially the western Balkans. Its role does not have to grow – bearing in mind the local and Russian-EU gas games and the cost and difficulties of developing regional infrastructure. The focus therefore needs to be on alternative sources of energy, including renewable energy, as the Cesec group is working on.

Agata Loskot-Strachota

More woe for Krk LNG

LNG Croatia has replaced its managing director for the third time in little over a year, and an open season for those wishing to book import capacity has been delayed. The project company, seeking to develop a floating LNG import terminal by 2020, has appointed Barbara Doric, formerly head of the national upstream regulator Croatian Hydrocarbon Agency, to replace Goran Francic, local news agency Total Croatia News reported April 20.

LNG Croatia told NGW early 2018 that it expected to take a final investment decision (FID) before the end of June. That might have made a project start-up late 2020 still viable but the timeline now looks in doubt.That’s because LNG Croatia itself said that it had postponed the deadline for final bids in its open season until June 22.

Although it said the postponement was because “interest in capacity booking was higher” than expected, and it had been asked for an extension, Total Croatia News reported a week ago that INA was the only company to have submitted one low-volume capacity bid by the original deadline earlier this month, already deferred once from mid-March. It is also unclear whether LNG Croatia has managed to procure an FSRU. In December 2017 the EU formally agreed to grant €101.4mn ($122mn) towards the project's total cost which was estimated earlier this year by LNG Croatia at around €360mn. LNG Croatia's current owners are Croatian electricity utility HEP and gas network operator Plinacro, both state-owned.

Mark Smedley