China en route to being world’s largest LNG import market [LNG Condensed]

China became the largest single gas importer in 2018 as demand again easily outstripped production. This raises two questions. How much more imported gas will it need in coming years, and how much will comprise LNG?

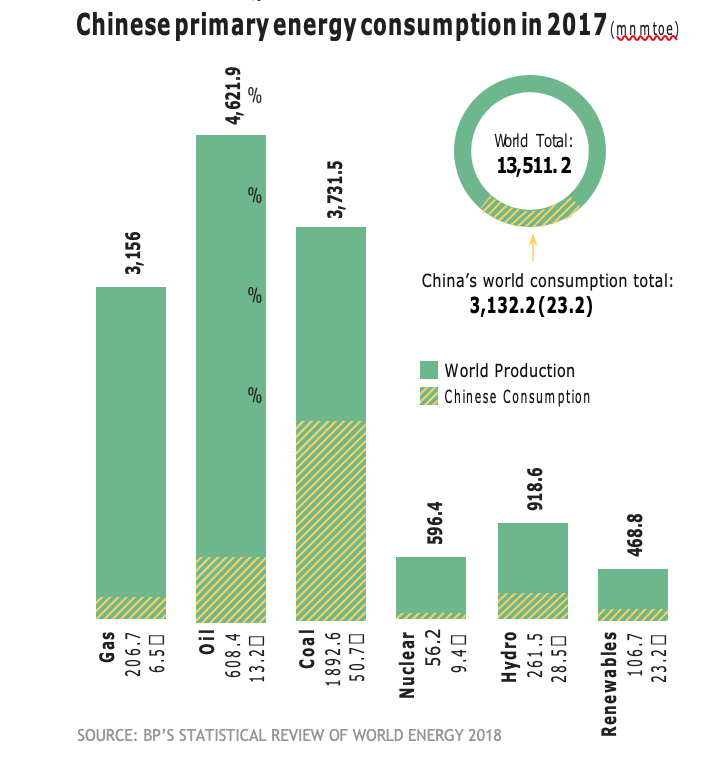

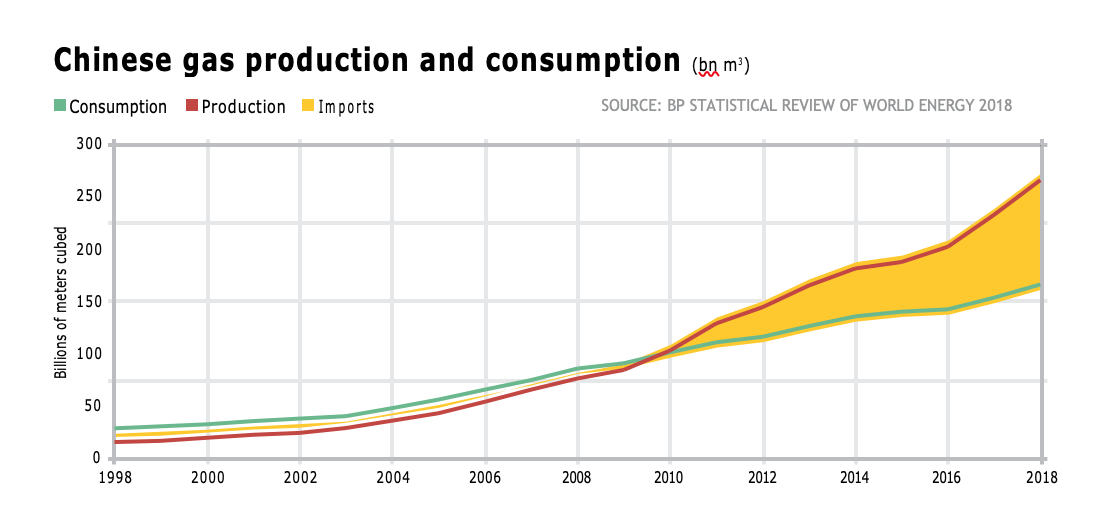

In 2017, China used 237.3bn m3 of gas, according to the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Production rose 7.2% year on year to 148.4bn m3 -- a higher increase than in previous years, but still well below demand growth of 12.8%.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

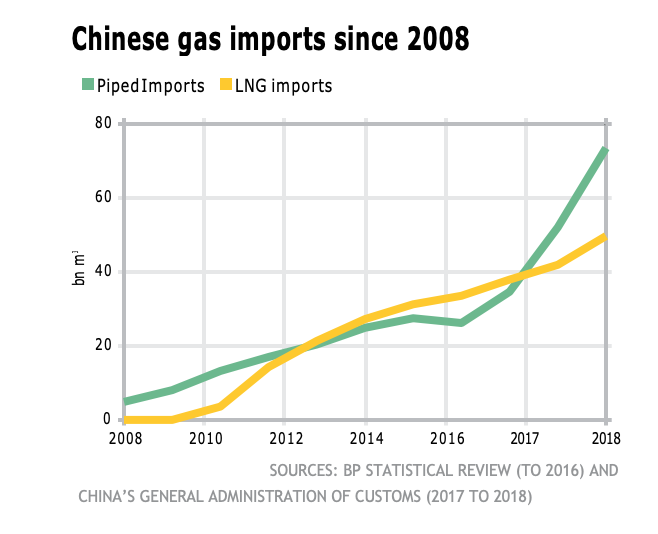

As a result, imports surged to fill the gap. Piped imports increased 10.5% year on year to 42bn m3, while LNG imports rose 46% to 51.8bn m3, making China the second-largest LNG importer after Japan.

In 2018, the pattern was the same with demand growth again outstripping robust increases in production. Gas output rose 7.5% to 161bn m3, according to the country’s statistical department, while demand was up 18.2% year-on-year in November to 251bn m3, which would imply annualised demand of about 274bn m3, a rise of more than 15%.

LNG imports surged again. General Administration of Customs figures for calendar 2018 show a 31.9% year on year rise in gas imports to almost 123bn m3. Within the total, LNG imports jumped about 40% to around 73bn m3.

Looking forward

More of the same can be expected as China rapidly evolves into the world’s largest LNG import market. The International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2018, published in November, projects a near-tripling in Chinese gas demand to 708bn m3 by 2040. Imports are projected to rise from 42% of gas supply in 2017 to 54% over this period.

China’s voracious demand for LNG over the next decade is expected to underpin global investment in LNG production capacity.

The IEA’s demand forecast for 2040 is about 100bn m3 higher than it projected just a year earlier. The increase was attributed primarily to Beijing’s environmentally-driven policy of switching residential and small-scale energy users from coal to gas. This started in 28 cities in northern China in 2017.

Moreover, the projected increase in gas import share and volumes to 2040 is front-end loaded. Imports are projected to account for over half gas supply as early as 2025, and to triple to 300bn m3 by 2030. With most gas import pipelines near capacity, and a long gestation period for new lines, satisfying the surge in gas needs over the next decade or so will rely mainly on LNG.

In terms of annual growth some of the steam will come out the current boom, but rates of demand growth will remain high. S&P Global Platts Analytics forecasts imports will grow 14% in 2019, while Wood Mackenzie anticipates growth of 20%.

The dampened growth rate is attributed by Wood Mackenzie to China’s “more considered approach” towards coal-to-gas switching, economic slowdown, and higher gas production and piped imports.

The more considered approach is a response to the situation that arose in winter 2017/18, when far more northern Chinese coal-fired heating systems were converted to gas than there was fuel to run them. This forced Chinese energy companies to search frantically for large volumes of LNG, pushing spot prices to stratospheric levels.

Lessons learned

The conversion programme has become more modest as a result, and there has been an increased focus on building sufficient gas storage capacity, integrating distribution systems and planning LNG procurement. Ahead of the current winter heating season NDRC and the state-linked energy companies CNOOC, CNPC and Sinopec sought to allay fears about gas supplies by detailing their plans, with NDRC noting that 120bn m3 would be available.

Unless offset by unexpectedly severe winter weather in China and northeast Asia, the change in approach will dampen growth and prices in the Asian LNG market in 2019. But in subsequent years the accuracy or otherwise of concerns about a Chinese economic downturn may prove a more important determinant of LNG demand and prices.

The concerns have been fed by a spate of gloomy economic indicators. Together these have been taken to indicate a further weakening of Chinese business and consumer sentiment already hit by the Sino-US trade war and domestic issues such as high debt. There have been reports that northern gas demand, particularly from industry, is lower this winter than contracted LNG volumes.

However, bleak numbers for car sales and other retail indicators may not presage a general economic downturn. China’s stock response to economic malaise is a bracing round of stimulus measures, with the energy-intensive infrastructure sector the main beneficiary. The latest round began in mid-2018 and is again building up, with a large number of transportation projects announced at year’s end.

The initial impact of the stimulus programme is indicated by electricity generation data, often a more reliable guide to Chinese economic conditions than GDP. Generation grew 6.8% year on year in 2018 -- higher than in the preceding four years, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. In this context it is worth noting that if gas-fired generation makes inroads into the coal-dominated power market, Chinese gas requirements could grow substantially even with subdued economic growth.

Gas production

If gas demand growth remains strong, where will the fuel come from? Gas production is generally projected to grow, with unconventional resources to the fore.

For instance, in September 2018, CNPC’s Economics and Technology Research Institute (Etri) projected demand growth of 5.8% a year to 620bn m3 in 2035. For the same year it forecast production of 300bn m3, split equally between conventional and unconventional resources, including shale gas, tight gas and coalbed methane.

Conventional output would be little higher than now, with new finds barely replacing depleting fields. Moreover, the strong projected growth for unconventional output, especially shale gas, assumes better progress than hitherto. Shale gas output grew to over 10bn m3 in 2018, but well below the rate needed to reach the targeted 30bn m3 in 2020 and 100bn m3 in 2030. Overall gas production of 300bn m3 by 2035 could thus prove optimistic.

Piped imports

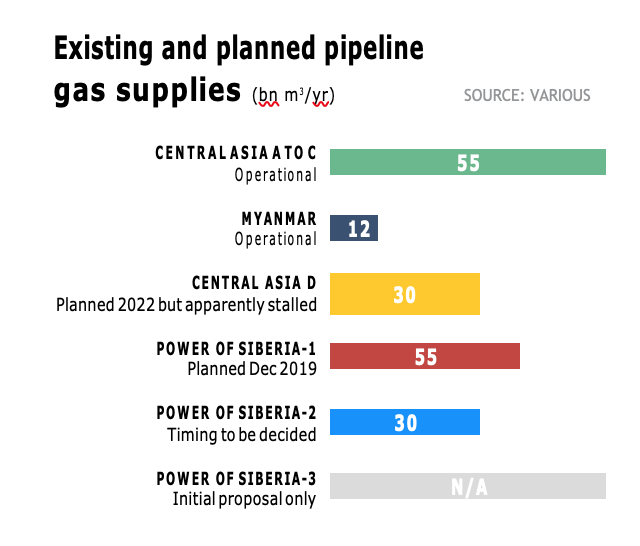

This puts the onus firmly on imports. The capacity of China’s import pipelines is 67bn m3/yr, with actual supply of about 51bn m3 in 2018. The 12bn m3 Myanmar line supplied about 4bn m3 and the three-pipe, 55bn m3 Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline system supplied 46.9bn m3 from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

Piped imports will jump when Russian gas starts flowing through the 38bn m3 Power of Siberia line-1 in 2020. Following that, the 30bn m3 Central Asia-D line is scheduled for completion from 2022. But the project appears to have stalled, with little apparent pressure to resume work at a time when Turkmenistan’s focus appears to have shifted west and south.

Meanwhile, another 30bn m3 line, Power of Siberia-2, has been under discussion with Russia since the mid-2010s. Gazprom Deputy CEO Alexander Medvedev said in December that negotiations were progressing, but gave no timetable for its implementation.

The slow progress is not surprising. Chinese negotiations on projects involving 30-year purchase commitments are invariably protracted, especially where there is potential for over-dependence on one supplier. While Russian President Vladimir Putin told the Russian-Chinese Energy Forum in November 2018 that “relations between the Russian Federation and People’s Republic of China are on the rise,” past precedent might suggest the current alignment of interests could prove temporary.

Piped imports in the mid-2030s could thus range from 105-165bn m3, depending on whether Central Asia-D and Power of Siberia-2 are built. Based on this range and Etri’s demand (620bn m3) and production (300bn m3) projections, LNG would be left to supply 155-215bn m3 in 2035.

LNG moves centre stage

While this is two to three times the 2018 level, installing the necessary LNG regasification capacity would be quite feasible. Almost 92bn m3 was operational at end 2018, with more under construction. In mid-January, preliminary government plans emerged for the expansion of LNG import capacity to 336bn m3/yr by 2035.

The additional capacity may be needed, since there is a real possibility Chinese LNG requirements in 2035 could be much higher than 215bn m3 for two reasons.

- Etri’s expectations for gas production may prove optimistic.

- Gas demand from households and other small-scale users switching from coal could be higher than expected as environmental concerns climb the list of priorities for both citizens and government.

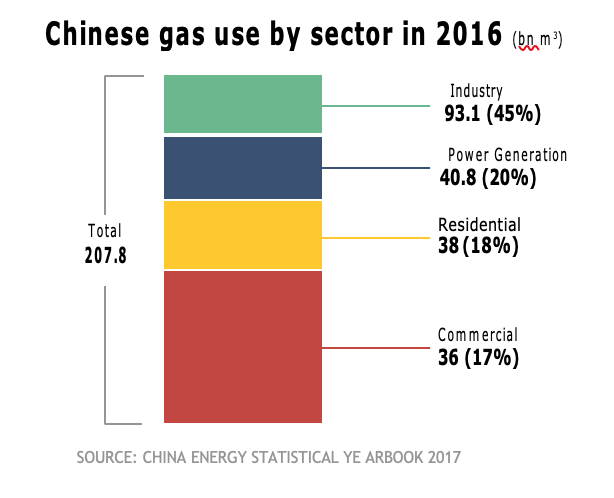

If the rapid growth in environmental concerns means coal use faces punitive measures, an even bigger upside factor for LNG could come into play. Gas-fired electricity generators currently account for less than 20% of Chinese gas use, hamstrung by its price relative to coal. If coal use were financially penalised or in places banned, electricity sector gas demand could surge. That would require a very large amount of additional LNG.

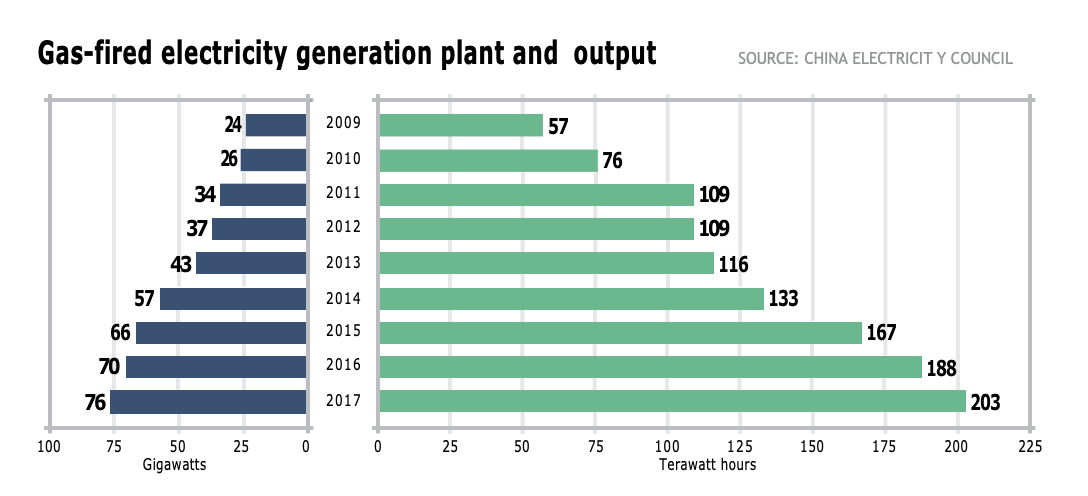

China’s 75.7 GW of gas-fired capacity in 2017 was only 4% of total capacity. And it operated at a load factor of barely 30%, producing 203 TWh or 3% of national generation.

Most forecasters expect power sector gas use will rise, not least because the stock of gas-fired plant is projected to increase by about half in the near to medium term. However, even a modest increase in plant utilisation could easily add 100bn m3 or more gas to that already projected. That would have to be supplied by LNG, taking potential LNG requirements in 2035 up to 315bn m3.

Sourcing this amount of LNG would not be insurmountable. About 82bn m3 of global LNG export capacity is set for final investment decisions in 2019 alone, according to Wood Mackenzie, with numerous other potential projects queuing up behind.

Chinese LNG use could thus exceed 300bn m3 by 2035. There is no certainty that the strong gas demand and import growth projected for the next few years will tail off. Constrained domestic production and pipeline imports combined with robust economic growth and environmental pressures could act as strong push factors for LNG imports well into the 2030s and beyond.

Like this article? Subscribe to our complimentary publication dedicated to LNG below (next Issue February 27, 2019:

|

LNG Condensed brings you independent analysis of the LNG world's rapidly evolving markets. Covering the length of the LNG value chain and the breadth of this global industry, it will inform, provoke and enrich your decision making. Published monthly, LNG Condensed provides original content on industry developments by the leading editorial team from Natural Gas World. LNG Condensed is your magazine for the fuel of the future. |

Sign up now to receive LNG Condensed monthly FREE

.png_f1920x300q80.jpg)